By Melissa Walsh

My guess is that the only thing I had ever said to anyone at Chung’s Restaurant was, “Hi. Pick up for Melissa.” Now three decades later, after reading Curtis Chin’s memoir about growing up at Chung’s, I wish that I had allowed curiosity to move me into initiating conversation with those who had served me there — the Chungs and Chins and the friends that worked for them. Who knows. Maybe Curtis Chin himself had on occasion handed me my carryout. Located on Cass and Peterboro in the Chinatown alcove of Detroit’s Cass Corridor, Chung’s was a culinary gem Detroiters prized. Many a local or Wayne State University newbie, like myself, cherished Chung’s egg rolls as the finest on-budget, tasty on-the-go meal around. Despite its location in an area famed for its crime stats and anecdotes — prostitution, drug trafficking, auto theft, arson, and murder, Chung’s served a loyal clientele for 40 years before closing in 2000 as Chinatown’s last Chinese restaurant in operation. Former patrons still remember Chung’s fondly, as demonstrated in online comments reacting to recent articles covering the May 17 purchase of the building. I suspect today’s contempo ilk of the rebranded “Midtown” would have loved Chung’s as much as we did back in the day. I recall driving along Cass looking for a parking spot near Chung’s and thinking, “Wow, hookers do NOT look like that in the movies.” This was one of many educational doses of reality the pre-gentrified Corridor gave me. Curtis Chin and his five siblings were raised with many more Corridor truths, guided by their grandparents and parents. In Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant, Curtis — aka “number three,” the third child — brings readers into his point of view and grounds them in the lessons he learned. “The most coveted seats were up front,” Chin shows us, “where five huge windows gave diners a full view of Detroit’s bustling Cass Avenue. At first, I thought these diners were picking those seats for the beautiful scenery. But then I realized they were watching their cars to make sure they weren’t stolen.” Chin witnessed the gradual disrepair of Detroit’s Chinatown and shares with us what that looked like with a child’s lens. As he and his siblings were the only American-born Chinese-American kids in the neighborhood, Chin felt an obligation to become “cultural ambassador” to help them assimilate, schooling them about Detroit’s Motown heritage and playing apologist of the practice of throwing fresh octopus on the ice at Joe Louis Arena. This early sense of self launches Chin’s early drive to figure out exactly who he is and how he fits in. The Chin family moved to the Detroit white middle-class suburb of Troy when Curtis and his older brothers were in secondary school. However, the Chin kids continued spending more time working and studying in their Detroit restaurant than they did attending school and sleeping in Troy. About the same time, Curtis also began becoming aware of his homosexual feelings. Chin shares anecdotes of the sting of racial prejudice he and his family experienced in the burbs and the inner struggle he quietly endured as he worked to untangle his sexual identity with no one to confide in. “One of the most important lessons I learned at the restaurant was about timing," Chin writes about coming out, "when to bring out the soup and egg rolls, when to pick up the dirty plates, when to put out the bill. Everything had an order. Nothing could be rushed.” Though Chin candidly addresses weighty topics, he thoroughly lightens the prose with humor. The memoir's entertaining laugh-out-loud elements push the reader to keep reading. What I loved most were Chin’s stories about his parents. With compassion and wit, he shows us the great depth of his parents’ devotion to their children and the tremendous wisdom that poured from them. I suppose that I had mistakenly assumed all those years ago that it was just the delicious egg rolls that made Chung’s so special. I understand better now. Detroiters adored Chung’s as a place of kindness. It was an oasis for students seeking a quiet place to study with a bottomless cup of tea; prostitutes needing a place to eat, freshen up, and breathe; hungry neighbors running a food tab that might not ever get paid; city of Detroit leaders looking for good, honest conversation. “Yes, my family succeeded because of America,” Chin writes, “but America also succeeded because of us.” I’ll stop here; I don’t want to give too much away from this outstanding memoir (release date October 17, 2023). I recommend that you read this book as soon as it’s available whether you had the pleasure of enjoying Chung’s during its 40-year run or not. Curtis Chin did the world a good service by capturing what his family taught him so well: “Work hard. Be quiet. Obey your elders.” In other words, Chin’s memoir shows us that honoring persistence, humility, and respect for others goes a long way. Learn more about Curtis Chin’s work here: Curtis from Detroit. © 2023 Melissa Walsh

0 Comments

By Melissa Walsh

Blue bounty flowing fancy, pilfering chore Harkening I awoke to voices bellowing mission Come hither Ahoy, delight in enchanting wonders, perilous Mariner I welcomed reverie captive in aqua pura Blue-green light Where true untamed science spins allegory Mermaid songs I hear chronicles of souls rescued, ships wrecked Shifty winds Confined by waters ungoverned by the moon Sailors toil I see captain watching, steering, hollering ‘Helm a lee’ ‘Lee oh’ over unknowns unbound underneath Finding groove I acquire lessons of uncertain science Instincts honed

A referee refused to shake my hand years ago while I was at the bench watching a youth hockey team warming up before a game. I was the team's head coach. I was wearing a coach's jacket. The players were little girls. He saw me and skated over.

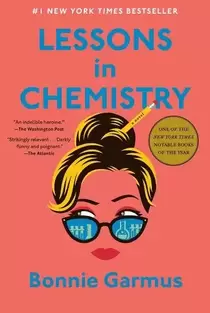

"No moms behind the bench," he said as I extended my hand. I thought he had come over to greet me with the customary ref-coach pre-game handshake. "I'm not their mom. I'm their coach," I said. He asked me to show him my USA Hockey Coaching Education Program (CEP) card to prove this to him. I got my wallet out and showed it. "Well, you know, I just don't need a mom over here screaming." "I am not their mom. And I don't scream." A bit later, he brought the scoresheet over and asked one my assistant coaches, a player's dad, to sign it. I took it. "I'll sign that." I returned the sheet to the ref. He gave me a nasty look, likely returning my nasty look at him, and skated off. I remember feeling so angry during that game. So frustrated with being treated unfairly. We were playing a boys' team and won that game. We won all but one game against the boys that season. It was the girls' teams we struggled to beat. We only won two games against them. But the win-loss record wasn't the point for my 8U hockey players. Their lessons in hockey were about so much more — how to jump out onto the ice when it's scary, how to skate as fast as you can to gain control of a loose puck, how to get up after getting knocked down, especially when an opposing player had rammed into you on purpose and the ref didn't even call a penalty. For me, the coaching experience became more lessons in standing up tall and keeping my mind in check after being hit with misogynic cheap shots. To be treated with a lack of respect and not as a thinking and feeling human being stings. It hurts. It can erode confidence and surface feelings of despair and defeat. How does a woman heal from this kind of treatment? Bonnie Garmus' novel Lessons in Chemistry is a lovely story about a highly intelligent woman finding her strength and not losing her mind while being knocked down hard — like from a two-hander slash — by old school, late 1950s and early 1960s misogyny.

By Melissa Walsh

If love is expressed by showing up and giving, then a whole lotta love filled Hamtramck’s (new) New Dodge Lounge for Mikeypalooza this past Saturday, when hundreds of Detroit rockers, locally and from out of state, arrived to help an old friend, Michael Karwowski, who is battling cancer. Alan Karwowski organized the event to raise support for his younger brother. The connection with old friends was exceptional, magical, as is Hamtramck Rock 'n' Roll — compelling rock styles (punk, glam, garage), maybe with hints of polka, or certainly a great appreciation for polka. For decades, the uncommon, memorable sounds of the Hamtramck music scene were nourished by Lili Karwowski and her five sons. Anyone who kicked their feet to rock and polka — not mutually exclusive tastes in Hamtramck (see Polka Floyd and The Polish Muslims) — from the late 1970s through the 1990s spent much of their free time at Lili’s 21, there on Jacob, right off Joseph Campau. (For you younger hipsters, this is The Painted Lady today.) If you’ve heard the fetching Polish Muslims song “Sophie Is a Polka Rocker,” then you know what kind of vibe I’m talking about. Lili Karwowski was Hamtramck’s most beloved polka rocker. I wasn't able to catch the action at Lili’s in the late 70s (still in middle school) and early 80s (still in high school, even though I occasionally had a beer at Paycheck's). I missed much of the mid- and late 80s away at college. I experienced the Lili’s 21 scene of the 90s. Good times. The venue was walking distance from my flat on Holbrook. I’d stroll over there with girlfriends whom I worked with at Gale Research; they also lived on Holbrook, where the rent was affordable for us newbie editors making under 20K a year. We were GenXers pursuing the party, wearing our fuzzy sweaters or avant-guarde t-shirts; tight jeans, spandex, or mini-skirts with fishnets or thigh-high black stockings (cool digs found at Tobacco Road or Showtime); and platform shoes or tall boots. We applied heavy eye-liner, not just around our eyes, but also lining our lips coated with a slightly less dark shade of lipstick. We teased out our hair and shellacked it with Aqua Net. For some warmth, we might slip on an over-sized blazer, flannel shirt, or snug leather jacket. Or maybe an animal-print faux-fur jacket or coat. I remember Lili complimenting the hipster fashionistas on their style while she sat there by the rear-side door collecting cover dollars. She was quite the fashionista herself. And I think we probably discovered our fondness for animal print from knowing Lili.

By Melissa Walsh

"... new life starts in the dark. Whether it is a seed in the ground, a baby in the womb, or Jesus in the tomb, it starts in the dark." ― Barbara Brown Taylor in Learning to Walk in the Dark It was days before our first Christmas without their dad, in our so-called “broken home.” My oldest son was three. My twin sons were two. The divorce was final the previous April. It was 2000. I grieved my marriage and the dreams that died with it. I was sleep-deprived; any sleep I could find came with crying myself into it. I was afraid for my and my sons’ future. I was in a darkness that comes with despair. Then a mysterious light broke through December 23, warming me in its power. Darkness and Light My church's divorce from me following my divorce from my husband made despair's darkness even colder. I hadn't stopped loving him. I did it as a last resort, after years of his lies, betrayals, apologies. I did it as a means of protecting our home and family from his addiction and the activities his addiction generated. I needed to protect our home from being taken due to his selling drugs, as an attorney in the church had told me, his advice unsolicited by me back in 1999. My pastor, whom I had confided in for counseling, had told this attorney, who also was a church elder, about my crisis. The irony, as I discovered when the divorce became final, was that the body of church elders (men, no women) also had discussed my situation and they came to a consensus of denouncing my decision. Whatever they had used as discovery did not include speaking with me. Perhaps they concluded that I had happily filed for divorce, that I had gleefully decided to go it alone with three babes and a full-time job. I was kicked out of a Sunday morning study group of congregants my age, a group I had founded with two friends years earlier. They loved the addict more than me, I learned later. Nonetheless, I continued bringing my sons to church each week, not an easy task walking past people I’d known for decades, who pretended not to see me, to drop the boys off in their toddler class and then walk to the sanctuary to sit alone in a pew, listening to sermons about Jesus: Jesus speaking with the Samaritan woman, Jesus' lesson of the widow’s mite, Jesus' teaching on the Beatitudes, and Jesus' humble birth to impoverished, unwed parents. I felt like a widow grieving the walking dead. I wore a veil, invisible to a world indifferent to my loss, concealing eyes that ached from crying. One only had to look me straight in the eye to see beyond the defiant veil, and three women in the church did. They looked and saw angst and heartbreak. An elderly woman I had never spoken with previously but had often seen over the years stopped me in the lobby as I was leaving the sanctuary one Sunday when the divorce was still raw. She led me to a private corner in an adjoining room. She burst into tears and hugged me. “I was married to an alcoholic,” she said. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed