America’s First Amendment guardians in 1920

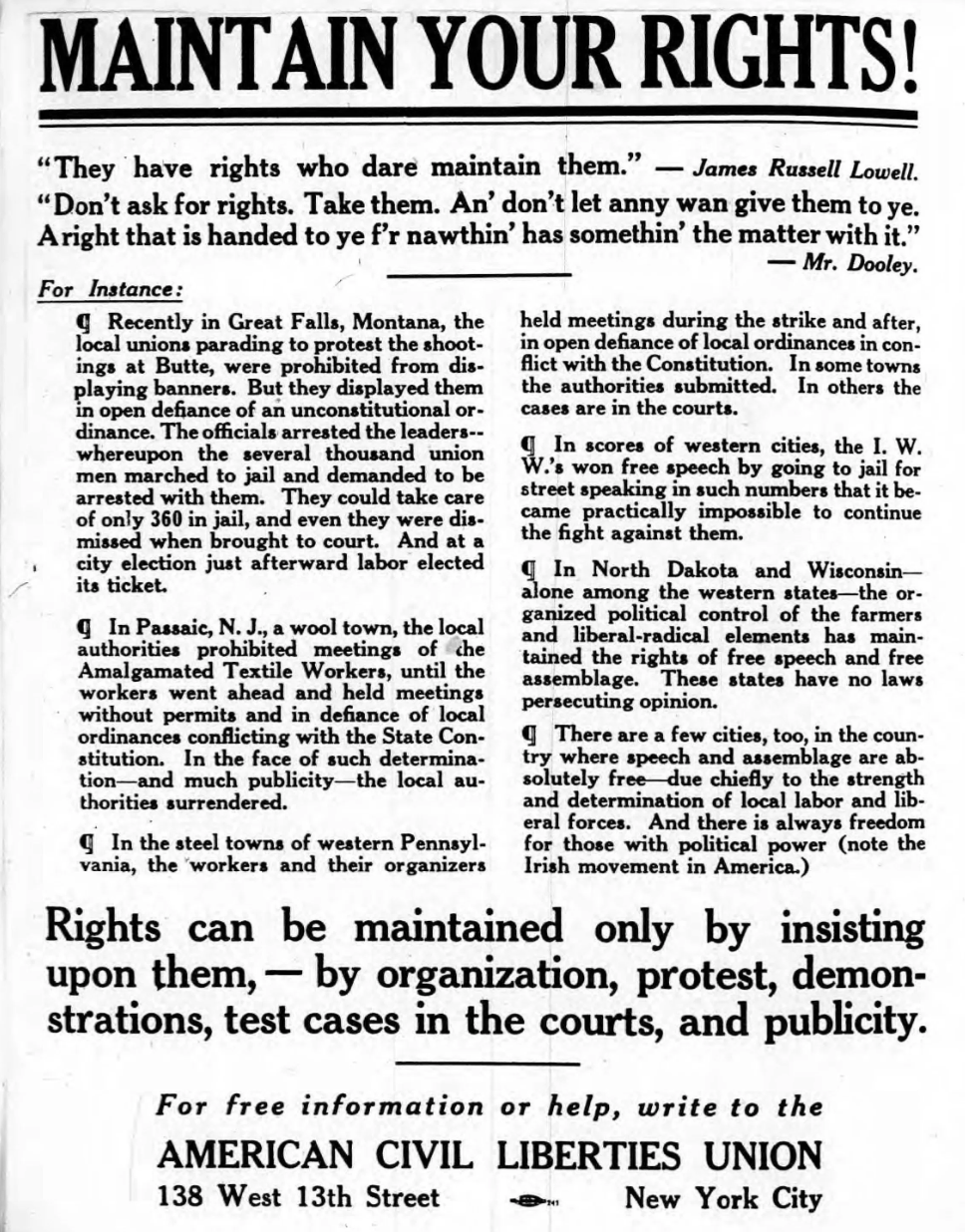

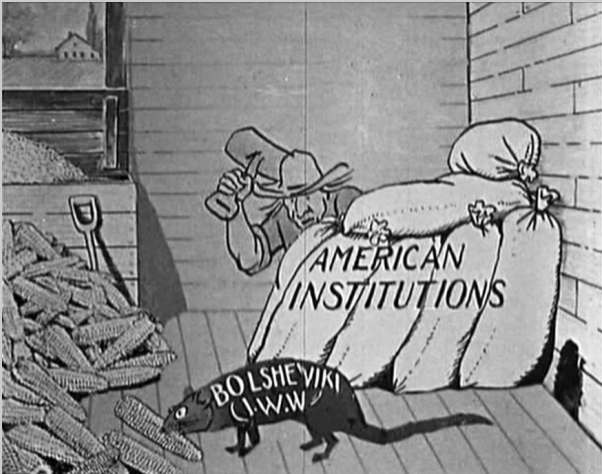

What I loved then and now about The United States is exactly this — the healthy pluralism of such encounters as mine on the campus of WSU, the right to have these conversations openly, the rights of leftists, and all of us, to gather and hand out literature. The First Amendment protects these rights. And our First Amendment watchdog is the ACLU, the organization born of the National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB), which was organized in 1917 to defend Great War (World War I) protestors and conscientious objectors. Founding members rebranded the mission in 1920 in response to the Palmer raids, viewing the activities of the DoJ as countering founding principles of the United States and in direct violation of the US Constitution, specifically the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. The ACLU’s founding members, per its first meeting minutes January 19, 1920, included Roger Baldwin, Crystal Eastman, Helen Keller, Walter Nelles, Morris Ernst, Albert DeSilver, Arthur Garfield Hays, Jane Addams, Felix Frankfurter, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Rose Schneidman. A hundred years later, the ACLU’s work has benefitted us all across the political spectrum. I can’t help but believe that if it weren’t for the ACLU, the Wayne States leftists I encountered 30 years ago would not have been permitted to discuss their views with me openly. Chances are I might have been persecuted for having studied and traveled in communist countries. Events in the United States — in Detroit — a hundred years ago illustrate how injustice strikes communities without the safeguarding of our First Amendment rights

0 Comments

Governor Whitmer signing Executive Order No. 2019-10. (Behind Gov. Whitmer, l to r): D.J. Hilson, Muskegon County Prosecutor and President, Prosecuting Attorneys Association of Michigan; Stephan Currie, Executive Director, Michigan Association of Counties; State Rep. Lee Chatfield, Speaker of the House; Lt. Gov. Garlin Gilchrist II; Chief Justice Bridget McCormack; and Attorney General Dana Nessel.

By Melissa Walsh

While covering city beats with the Grosse Pointe News, I learned how vulnerable many can become to arrest and incarceration, especially those with low income. For instance, many of the police reports I read as part of my reporting detailed arrests of drivers pulled over after their license plate had been scanned by a public safety officer while driving along Lake Shore Drive. I recall the report of a young mother being pulled over for expired auto insurance. She had not been speeding. She hadn’t run a red light or made an illegal turn. The officer had simply discovered by running her plate that her insurance coverage had expired just days earlier. The officer arrested her. She had her two toddler-aged children in the car and told the officer she was on her way to drop them off at day care before heading to her job in Grosse Pointe. The officer allowed her to call her husband. When he arrived, he was arrested for the same offense — driving with expired auto insurance. A relative picked up the kids at the police station while the two were in custody. Of course, a law enforcement officer who discovers the infraction and releases the offender is potentially liable if they were to cause an accident following the release. I get that. Yet the couple I mentioned above did not demonstrate being a threat to society. And yet, for missing a premium payment, they were facing the financial quicksand of court fines and fees, in addition to missing work and the trauma of their children witnessing their arrest. I read about many arrests like this one, which, from the perspective of common sense, seem unreasonable. Is jail being used to protect society? Or are the lives of too many arrestees upset with job loss and financial hardship caused by a justice system that counters a smart approach to justice? The problem of the accelerated rates of arrest and incarceration over the past few decades, especially among low-income populations, caught the scrutiny of the ACLU, which launched its national Campaign for Smart Justice in 2018. With volunteers investigating the arrest and incarceration systems and statistics in each of the nation’s 50 states, the ACLU aims to examine the issues and promote criminal justice reform. In early 2019, Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer issued Executive Order 2019-10, which created the Michigan Joint Task Force on Jail and Pretrial Incarceration, which went to work from April to November 2019 to investigate Michigan's justice system and determine its failures and best practices, including alternatives to plunging an individual into a whirlwind of court fines and fees (ie. tether and drug-test fees) and probation and incarceration that only the wealthy can avoid. Their findings were released on January 14, 2020.

Preparing for Prohibition

Late 1919, local authorities and residents were gearing up for the Volstead Act to go into effect January 1, 2020. Though the prohibition of alcohol for consumption had gone into effect in Michigan in May 1917, Detroiters enjoyed a supply from neighboring Ohio. With the Volstead Act drying up all U.S. states, Detroit’s bootleggers turned to a supply chain from Canada. And many of Detroit's doctors had been writing prescriptions for whiskey, which would be filled in Windsor pharmacies just across the Detroit River. The Canadian government had announced on December 10, 1919 that it would lift its war-time prohibition on alcohol (and horse-racing) effective January 16, 2020 and granted amnesty to offenders who were criminalized while the act had been in effect. The manufacturing of liquor would be permitted for shipment from one province to the other. This restricted the sale of intoxicants, but opened up the means, per export permit, for Detroit's neighbors in Windsor to have liquor delivered to their homes for “private consumption.” We know from history that bootleggers, like the Purple Gang, took advantage of this policy to illegally transport Canadian whiskey from Windsor over the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair into Detroit, the Downriver communities and St. Clair Shores. So in 1919, while bootlegging opportunists like the Purple Gang were setting up logistics for importing bonafide Canadian whiskey, other less-sophisticated operators were selling low-grade moonshine. On December 27, 78 deaths were reported in four states (Michigan was not among them) within 48 hours from drinking “fake rum,” which was actually wood alcohol with brown coloring to pass as whiskey. Though Detroiters were spared this tragedy — still enjoying ample, though costly and illegal (but legal from a pharmacy), supply of genuine whiskey -- the move to crack down on alcohol distribution was ramping up by state and federal law enforcement. This led to a series of raids. It was difficult for Detroiters to discern from legitimate law enforcement agents from thieves. For example, the Christmas Eve edition of the Detroit Free Press reported that men posing as state food and drug enforcers seized 8 gallons of “Christmas cheer” from a Detroit man’s cellar. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed