|

By Melissa Walsh Following an event for a young political candidate, I commented to a news colleague, “How about these millennials? Impressive.” “Yeah, our generation really dropped the ball,” she responded. She’s an older gen-Xer like me, born close to that arbitrary Baby Boomer cutoff. Will this generation “undragon” us, I wondered, peeling away the dragon scales covering our nation’s founding enlightenment aims of civil liberties and justice? Was a major tear, ripping into America’s heart of power, the 2018 March for Our Lives movement, this generation of youth’s response to the killing of 17 students at the hands of a gunman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla.? In 2019, did teen activist Greta Thunberg remove a layer of scales that were apathetic to the threat of climate change? Will we remove national scales of indifference to catastrophes abroad while quarantined by the 2020 Coronavirus landing in our neighborhoods? The notion of being undragoned was a metaphor employed by C.S. Lewis in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, from the The Chronicles of Narnia. The story’s principle character is a greedy, lazy boy named Eustace, who lands in Narnia. Seeking to avoid the joyful, unselfish Narnian community and its work, Eustace sneaks off to an old dragon’s den for repose. When he falls asleep “on a dragon’s hoard with greedy, dragonish thoughts in his heart, he has become a dragon himself.” Dragons are selfish monsters that feed off the flesh of other dragons, animals and humans. When Eustace finds he’s a dragon, at first he’s pleased with new power to enact revenge against those he dislikes. But soon Eustace experiences the loneliness of being a monster. A lion sees Eustace crying and summons him to a well. The lion tells him to undress and get into the water. Wearing no clothing, Eustace attempts to remove the ugly dragon scales covering him. Multiple times, he peels away a layer of scales, only to reveal another deeper layer. Finally, the lion says, “Let me undress you.” The lion tears away the layers with his claws. The first tear is the most painful, ripping right into Eustace’s heart. When the scales are removed, Eustace climbs into the water. It hurts, but he is undragoned and sees his true identify as a boy. Lewis’ story is about personal, spiritual reform. The transition from self-love to loving others is the process an individual undergoes in realizing his or her best self, Lewis believed. He called undragoning the “radical surgery” of allowing virtue to free us into our true selves; it is painful, necessitating risk, vulnerability and faith in goodness. The virtue for undragoning America into its best self is civil reform, articulated in our Constitution and Bill of Rights. Events cause us to examine the first two amendments in the Bill of Rights. We see high school students applying the First Amendment to bring clarity of how the Second Amendment ought to be interpreted. We see those interpreting the right to “a well-regulated militia” and “to keep and bear arms” as the right of civilians to purchase weapons designed for combat. We see some with this view attacking speech of the students. We see political actors accusing the media of politicizing the Coronavirus pandemic with so-called scare tactics as reporters share verifiable data on the spread of the virus. We see fearful consumers hoarding toilet paper, sanitizer, cleaning wipes, bottled water, canned goods, and Coca Cola. Only those with disposable income can afford this hoarding. Meanwhile, those living paycheck to paycheck face empty shelves. We are dragoned. Our nation’s founders would urge us to allow civic virtue to peel away the layers of America’s self-aggrandizement-at-all-costs dragoning. They would call on a reawakening of the civil liberties on which this nation was built — what made America great. Achieving community of harmonious peace, they might add, requires more than flatly following stipulations written into and amended to our constitution; it requires good acts and just policies, trumping any individual’s or group’s right to trample on the common good of protecting us from ourselves and to feed the dysfunction in our nation leading to murders of young people at Columbine High School, Virginian Tech, Sandy Hook Elementary School, Stoneman Douglas High School and on our city streets. And these days, sadly, voices of moral courage (and common sense) must check the greedy, who would prefer a robust economy over protecting the most vulnerable to succumbing to the Coronavirus pandemic. As citizens in community, let’s examine how we treat our children and teens. How about our elderly? Do we blame the poor for the crises they face? What about the sick without health insurance? Do we really believe in rehabilitation for the imprisoned? Why do we allow unequal “justice” for the wealthy and the poor? For those applying our First Amendment right of freely practicing a faith, isn’t there room for a Golden Rule-like force in politics? How about giving to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s? Or what about not pursuing dishonest gain, but being eager to serve? The lyric in “Talk Talk” by Perfect Circle cries out: “You’re waiting on miracles. We’re bleeding out. Thoughts and prayers, adorable, like cake in a crisis. We’re bleeding out. While you deliberate, bodies accumulate.” In his book “Generous Justice,” theologian Tim Keller said human community is only strong when individuals weave and reweave themselves into it, strengthening it — not only with sharing, understanding, mercy and love — but our souls, our unique ideas, experiences, talents. This is how shalom — or harmonious peace — is achieved. The individual knows his or her true north for discovering good purpose and weaves that good into society, engaging with others in their good purpose. Good purpose is not “safe,” but it is right and will make America civil again. Let’s undragon ourselves as individuals in community, liberating the soul of American politics from the bondage of pride, fear, greed, hate, and complacency. © 2020 Melissa Walsh

0 Comments

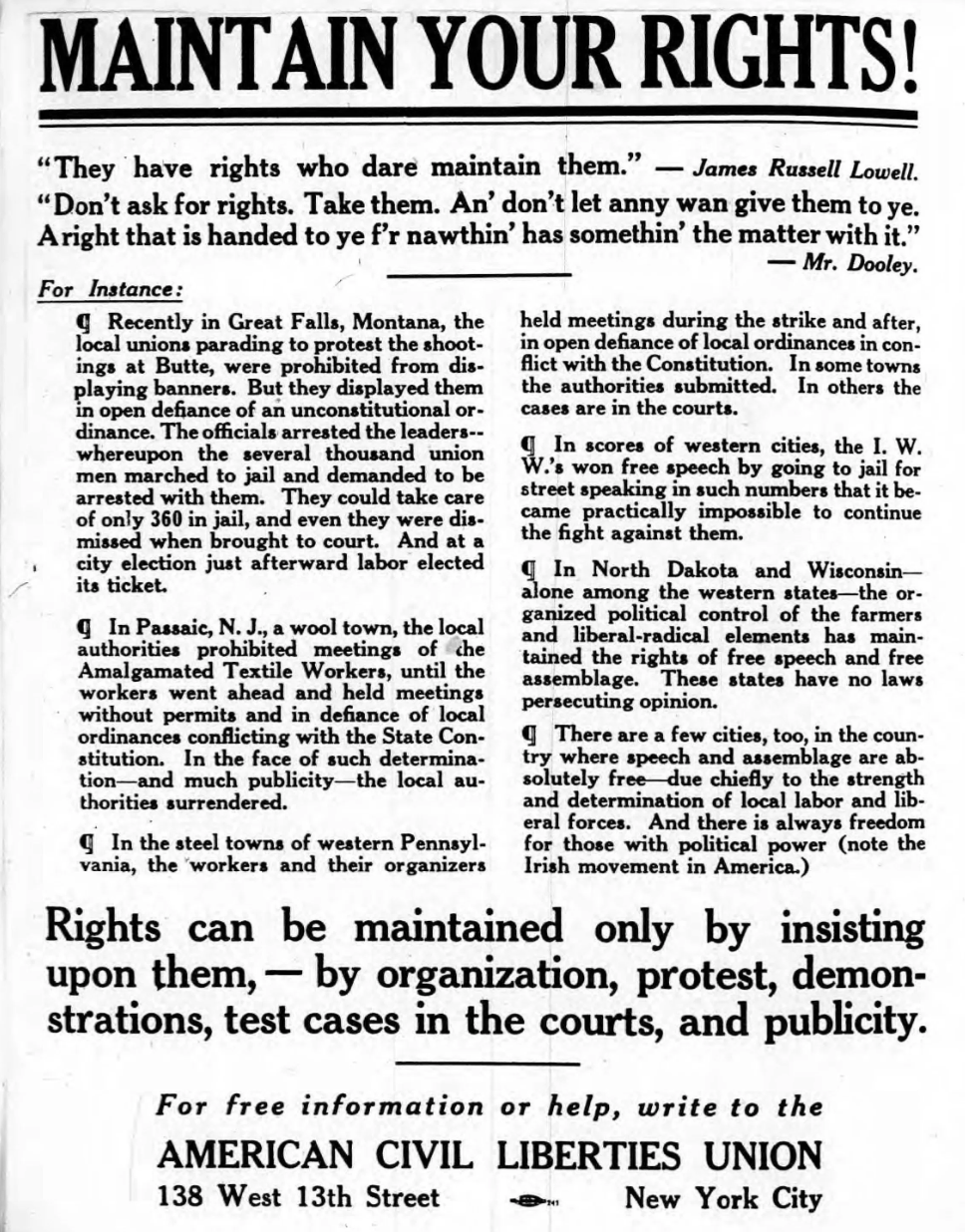

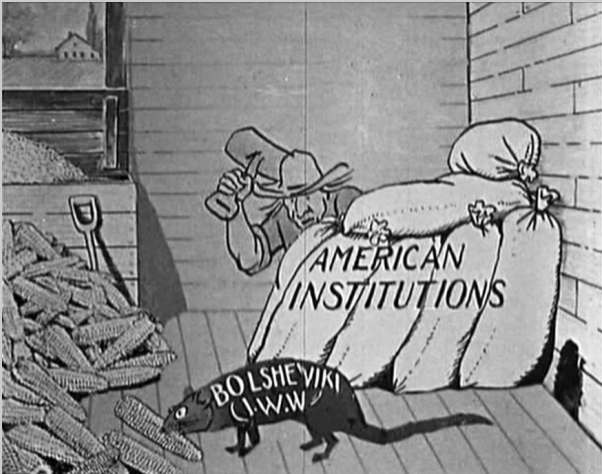

America’s First Amendment guardians in 1920

What I loved then and now about The United States is exactly this — the healthy pluralism of such encounters as mine on the campus of WSU, the right to have these conversations openly, the rights of leftists, and all of us, to gather and hand out literature. The First Amendment protects these rights. And our First Amendment watchdog is the ACLU, the organization born of the National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB), which was organized in 1917 to defend Great War (World War I) protestors and conscientious objectors. Founding members rebranded the mission in 1920 in response to the Palmer raids, viewing the activities of the DoJ as countering founding principles of the United States and in direct violation of the US Constitution, specifically the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. The ACLU’s founding members, per its first meeting minutes January 19, 1920, included Roger Baldwin, Crystal Eastman, Helen Keller, Walter Nelles, Morris Ernst, Albert DeSilver, Arthur Garfield Hays, Jane Addams, Felix Frankfurter, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Rose Schneidman. A hundred years later, the ACLU’s work has benefitted us all across the political spectrum. I can’t help but believe that if it weren’t for the ACLU, the Wayne States leftists I encountered 30 years ago would not have been permitted to discuss their views with me openly. Chances are I might have been persecuted for having studied and traveled in communist countries. Events in the United States — in Detroit — a hundred years ago illustrate how injustice strikes communities without the safeguarding of our First Amendment rights

Preparing for Prohibition

Late 1919, local authorities and residents were gearing up for the Volstead Act to go into effect January 1, 2020. Though the prohibition of alcohol for consumption had gone into effect in Michigan in May 1917, Detroiters enjoyed a supply from neighboring Ohio. With the Volstead Act drying up all U.S. states, Detroit’s bootleggers turned to a supply chain from Canada. And many of Detroit's doctors had been writing prescriptions for whiskey, which would be filled in Windsor pharmacies just across the Detroit River. The Canadian government had announced on December 10, 1919 that it would lift its war-time prohibition on alcohol (and horse-racing) effective January 16, 2020 and granted amnesty to offenders who were criminalized while the act had been in effect. The manufacturing of liquor would be permitted for shipment from one province to the other. This restricted the sale of intoxicants, but opened up the means, per export permit, for Detroit's neighbors in Windsor to have liquor delivered to their homes for “private consumption.” We know from history that bootleggers, like the Purple Gang, took advantage of this policy to illegally transport Canadian whiskey from Windsor over the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair into Detroit, the Downriver communities and St. Clair Shores. So in 1919, while bootlegging opportunists like the Purple Gang were setting up logistics for importing bonafide Canadian whiskey, other less-sophisticated operators were selling low-grade moonshine. On December 27, 78 deaths were reported in four states (Michigan was not among them) within 48 hours from drinking “fake rum,” which was actually wood alcohol with brown coloring to pass as whiskey. Though Detroiters were spared this tragedy — still enjoying ample, though costly and illegal (but legal from a pharmacy), supply of genuine whiskey -- the move to crack down on alcohol distribution was ramping up by state and federal law enforcement. This led to a series of raids. It was difficult for Detroiters to discern from legitimate law enforcement agents from thieves. For example, the Christmas Eve edition of the Detroit Free Press reported that men posing as state food and drug enforcers seized 8 gallons of “Christmas cheer” from a Detroit man’s cellar. Every human generation has its own illusions with regard to civilizations; some believe they are taking part in its upsurge, others that they are witnesses of its extinction. In fact, it always both flames and smolders and is extinguished, according to the place and angle of views.

By Melissa Walsh

Burek and baklava. Giant juicy black grapes and luscious red tomatoes. Old men wearing the red fez selling Turkish coffee pots in the baščaršija, "marketplace." Olympic gold-winning champion basketball players at the cafe. Stars of Sarajevo’s popular rock band Bijelo Dugme at Obično Mijesto, or “Usual Place” — a bar in the baščaršija beloved by Sarajevo’s hipsters. And the cafe bar called Broj Jedan, or “Number One," set in a well-to-do neighborhood in the edge of the valley, where the politically well-connected lived. These are among my countless memories of Sarajevo. While I was a student at the University of Sarajevo in 1988, nearly each evening, for sure each weekend evening, I was among hundreds of young Sarajevans walking to the “meeting place” on Maršala Tita Ulica, "Marshal Tito's Street," where those in their late teens and 20-somethings greeted each other with Vozdra -- Sarajevan pig latin for “hi,” or Zdravo, “hello,” transposed. Vozdra, gde si? they’d say. Particular to Sarajevo was the pronunciation of Gde si?, or literally, “Where are you?” This was slang for "How are you doing?" Sarajevan youth did not pronounce gde with the prescribed hard g and hard d, but as a soft consonant blend. So to American ears, Gde si? sounded like the name "Jessie." When I uttered the greeting in the way of a Sarajevan youth, my friends would laugh. It was much like how I would react if a foreigner in my home town of Detroit greeted me with,” Yo, whadup doe?” Walking to or from the meeting place, one would pass soldiers buying kolaći, “sweets” for gypsy kids begging in the streets. They might take Principov Most, “Princip’s bridge” to cross the Miljacka River, where the first shot of World War I was fired. They might walk past the famous Sarajevo library or travel by street car past the yellow Holiday Inn and other modern buildings with a similar hideous and boldly modern aesthetic. I started from 127-A Lenjinova, an apartment building in the Grbavica section of Sarajevo, across the Miljacka from the University of Sarajevo’s Filosofki Falkutet, or School of Philosophy, where I was a student. I rented a room from a widow caring for her elderly mother and two grown sons who had finished university and were looking for work. My friends in the building included Nik, Milica, Bogdana, Nina, Igor, Goran, and Maja. They identified as Yugoslavs. Everyone I met in Sarajevo from 1987 to 1989 identified as a Yugoslav. I did not know that I was encountering a Sarajevan Yugoslav civilization in danger of extinction. The Sarajevo unity I witnessed was not an experiment. It was not a powder keg of hate. I experienced first-hand Sarajevo’s celebration of East and West — European- and Asian-influenced literature, music, and food. I witnessed close relationships between Sarajevan and Sarajevan, not between Croat and Serb, or Serb and Muslim, or Muslim and Croat. These relationships were caught in the anxiety of 40-percent unemployment among those under age 25, coupled with sky-rocketing inflation. The Sarajevo that I was first introduced to in 1987 and last visited in 1989 was a vibrant community of talented and well-educated individuals who identified as Yugoslavs. They were not hostile. They did not talk about their ethnic and religious family history unless I asked them about it. My circle of friends celebrated both Catholic and Orthodox Christmas, which are two weeks apart, Islam’s Ramadan, and communism’s May Day. They displayed Tito’s image somewhere in their apartment. They toasted each other with živeli, “to life,” or literally “(we) lived.” They laughed and added the Partisan toast of their parents who survived World War II, Smrt fascismo, slobodo naradu, “Death to fascism, freedom to the people.” I couldn’t foresee fascism about to attack this great valley of cultural diversity and national unity within two years. But I knew a man who saw through the illusion I believed in. Twenty-nine years later, in 2018, I encountered Prague’s free-market make-over while traveling with my sons. It was stunning.

Photos by Melissa Walsh.

By Melissa Walsh

While a wave of revolution swept Eastern Europe 30 years ago, I was completing my degree in International Studies in Sarajevo and Vienna. During that time, I also traveled to Krakow and Warsaw, Poland, and to Prague, Czechoslovakia, participating in short-term study programs. This month, November 2019, as I’m compiling a memoir about my years abroad during the late 1980s, I’m consumed with nostalgia from my three visits to Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic. The first was while in transit to Poland by train in March 2019. The next was five days in Prague in April 1989. And the most recent was in July 2018, when I spent three days in Prague with two of my sons. But why is this month special? In addition to marking the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9), this month commemorates 30 years of democracy in the former Czechoslovakia (which in 1993 became the Czech Republic and Slovakia). Czechoslovakia had been a communist country since 1948. A series of reforms in the 1960s and a period of strikingly liberal revisions in 1968, known as Prague Spring, which included rolling back censorship, prompted the August 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia by troops from Warsaw Pact countries. A tight Eastern-bloc hold on Czechoslovakia remained for two decades. Czechoslovakia’s November 1989 Velvet, or Gentle, Revolution, began on November 17 with a student demonstration honoring International Students’ Day — a commemoration of the 1939 student demonstration against the Nazis, during which 1,200 Czech students were sent to concentration camps and nine were executed. The demonstration spawned additional anti-government protests over the next ten days, including a wide-reaching, nation-wide general strike on November 27. On November 28, 1989, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia announced the end of the party’s monopoly of power. Days later, the constitution was revised and the borders opened. On December 29, 1989, well-known playwright and political dissident Václav Havel became President of Czechoslovakia. The first two times I was in Czechoslovakia, in 1989, Havel was in prison.

In his memoir To the Castle and Back, Václav Havel called the 1989 revolution, described in the video below, “a drama in several acts.”

Havel had been active in advocating for liberal reform that led to the Prague Spring in 1968. With the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia the following August, his passport was seized and his plays were banned. Havel continued advocating for human rights, resulting in several arrests and a four-year imprisonment (1979-1983). By this time, Havel was recognized domestically and abroad as an important political dissident and crusader for human rights, earning him the Erasmus Prize in 1986.

Havel was sentenced to nine months in prison on February 21, after being accused and convicted of organizing a January 1989 anti-Communist demonstration, during which Charter 77 dissident activists laid flowers at the memorial of Jan Palach — the young man who burned himself alive in January 1969 in protest to the 1968 Warsaw Pact occupation of Czechoslovakia. He was released early from prison on May 17, 1989. In late March 1989, I was on a train from Vienna to Krakow, passing through Czechoslovakia. I remember my luggage being searched by police. Everyone’s was. The police also removed the ceiling panels in the train compartment and searched there. They searched everywhere. It was a tense experience. I also remember chatting with two Czechoslovakian guys about my age. I was 21. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed