By Melissa Walsh

My guess is that the only thing I had ever said to anyone at Chung’s Restaurant was, “Hi. Pick up for Melissa.” Now three decades later, after reading Curtis Chin’s memoir about growing up at Chung’s, I wish that I had allowed curiosity to move me into initiating conversation with those who had served me there — the Chungs and Chins and the friends that worked for them. Who knows. Maybe Curtis Chin himself had on occasion handed me my carryout. Located on Cass and Peterboro in the Chinatown alcove of Detroit’s Cass Corridor, Chung’s was a culinary gem Detroiters prized. Many a local or Wayne State University newbie, like myself, cherished Chung’s egg rolls as the finest on-budget, tasty on-the-go meal around. Despite its location in an area famed for its crime stats and anecdotes — prostitution, drug trafficking, auto theft, arson, and murder, Chung’s served a loyal clientele for 40 years before closing in 2000 as Chinatown’s last Chinese restaurant in operation. Former patrons still remember Chung’s fondly, as demonstrated in online comments reacting to recent articles covering the May 17 purchase of the building. I suspect today’s contempo ilk of the rebranded “Midtown” would have loved Chung’s as much as we did back in the day. I recall driving along Cass looking for a parking spot near Chung’s and thinking, “Wow, hookers do NOT look like that in the movies.” This was one of many educational doses of reality the pre-gentrified Corridor gave me. Curtis Chin and his five siblings were raised with many more Corridor truths, guided by their grandparents and parents. In Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant, Curtis — aka “number three,” the third child — brings readers into his point of view and grounds them in the lessons he learned. “The most coveted seats were up front,” Chin shows us, “where five huge windows gave diners a full view of Detroit’s bustling Cass Avenue. At first, I thought these diners were picking those seats for the beautiful scenery. But then I realized they were watching their cars to make sure they weren’t stolen.” Chin witnessed the gradual disrepair of Detroit’s Chinatown and shares with us what that looked like with a child’s lens. As he and his siblings were the only American-born Chinese-American kids in the neighborhood, Chin felt an obligation to become “cultural ambassador” to help them assimilate, schooling them about Detroit’s Motown heritage and playing apologist of the practice of throwing fresh octopus on the ice at Joe Louis Arena. This early sense of self launches Chin’s early drive to figure out exactly who he is and how he fits in. The Chin family moved to the Detroit white middle-class suburb of Troy when Curtis and his older brothers were in secondary school. However, the Chin kids continued spending more time working and studying in their Detroit restaurant than they did attending school and sleeping in Troy. About the same time, Curtis also began becoming aware of his homosexual feelings. Chin shares anecdotes of the sting of racial prejudice he and his family experienced in the burbs and the inner struggle he quietly endured as he worked to untangle his sexual identity with no one to confide in. “One of the most important lessons I learned at the restaurant was about timing," Chin writes about coming out, "when to bring out the soup and egg rolls, when to pick up the dirty plates, when to put out the bill. Everything had an order. Nothing could be rushed.” Though Chin candidly addresses weighty topics, he thoroughly lightens the prose with humor. The memoir's entertaining laugh-out-loud elements push the reader to keep reading. What I loved most were Chin’s stories about his parents. With compassion and wit, he shows us the great depth of his parents’ devotion to their children and the tremendous wisdom that poured from them. I suppose that I had mistakenly assumed all those years ago that it was just the delicious egg rolls that made Chung’s so special. I understand better now. Detroiters adored Chung’s as a place of kindness. It was an oasis for students seeking a quiet place to study with a bottomless cup of tea; prostitutes needing a place to eat, freshen up, and breathe; hungry neighbors running a food tab that might not ever get paid; city of Detroit leaders looking for good, honest conversation. “Yes, my family succeeded because of America,” Chin writes, “but America also succeeded because of us.” I’ll stop here; I don’t want to give too much away from this outstanding memoir (release date October 17, 2023). I recommend that you read this book as soon as it’s available whether you had the pleasure of enjoying Chung’s during its 40-year run or not. Curtis Chin did the world a good service by capturing what his family taught him so well: “Work hard. Be quiet. Obey your elders.” In other words, Chin’s memoir shows us that honoring persistence, humility, and respect for others goes a long way. Learn more about Curtis Chin’s work here: Curtis from Detroit. © 2023 Melissa Walsh

0 Comments

By Melissa Walsh

If love is expressed by showing up and giving, then a whole lotta love filled Hamtramck’s (new) New Dodge Lounge for Mikeypalooza this past Saturday, when hundreds of Detroit rockers, locally and from out of state, arrived to help an old friend, Michael Karwowski, who is battling cancer. Alan Karwowski organized the event to raise support for his younger brother. The connection with old friends was exceptional, magical, as is Hamtramck Rock 'n' Roll — compelling rock styles (punk, glam, garage), maybe with hints of polka, or certainly a great appreciation for polka. For decades, the uncommon, memorable sounds of the Hamtramck music scene were nourished by Lili Karwowski and her five sons. Anyone who kicked their feet to rock and polka — not mutually exclusive tastes in Hamtramck (see Polka Floyd and The Polish Muslims) — from the late 1970s through the 1990s spent much of their free time at Lili’s 21, there on Jacob, right off Joseph Campau. (For you younger hipsters, this is The Painted Lady today.) If you’ve heard the fetching Polish Muslims song “Sophie Is a Polka Rocker,” then you know what kind of vibe I’m talking about. Lili Karwowski was Hamtramck’s most beloved polka rocker. I wasn't able to catch the action at Lili’s in the late 70s (still in middle school) and early 80s (still in high school, even though I occasionally had a beer at Paycheck's). I missed much of the mid- and late 80s away at college. I experienced the Lili’s 21 scene of the 90s. Good times. The venue was walking distance from my flat on Holbrook. I’d stroll over there with girlfriends whom I worked with at Gale Research; they also lived on Holbrook, where the rent was affordable for us newbie editors making under 20K a year. We were GenXers pursuing the party, wearing our fuzzy sweaters or avant-guarde t-shirts; tight jeans, spandex, or mini-skirts with fishnets or thigh-high black stockings (cool digs found at Tobacco Road or Showtime); and platform shoes or tall boots. We applied heavy eye-liner, not just around our eyes, but also lining our lips coated with a slightly less dark shade of lipstick. We teased out our hair and shellacked it with Aqua Net. For some warmth, we might slip on an over-sized blazer, flannel shirt, or snug leather jacket. Or maybe an animal-print faux-fur jacket or coat. I remember Lili complimenting the hipster fashionistas on their style while she sat there by the rear-side door collecting cover dollars. She was quite the fashionista herself. And I think we probably discovered our fondness for animal print from knowing Lili.

By Melissa Walsh As I write this, leaders and healthcare workers of my home community of metro Detroit, and other communities around the nation, are faced with rising casualty counts due to the spread of the novel coronavirus COVID-19. In the past 24 hours, 1,719 new cases were reported in Michigan 78 Michiganders died, most of them in the tri-county area of metro Detroit, tallying 337 deaths. In the state, 9,334 people are infected. The virus is in the air, as is fear. Now we can imagine the horror faced in the fall of 1918, when Detroit's Department of Health reported 18,066 cases of influenza between October 1 and November 20, during which 1,688 people died. The disease reemerged in December and continued throughout January 1919. Another 10,920 cases were reported by late February 1919. What's especially eery, is that Michigan's rate of increase of contraction of disease from COVID-19 infection and rate of flu-induced death in March 2020 are uncannily similar to the numbers released by the state in October 1918 due to the spread of the Spanish flu. Like today's spread of the Covid-19 flu virus, the Spanish flu virus hit hardest in the state in Detroit and its surrounding suburbs. What Detroit history of fall of 1918 teaches us is that the rescindment of closure of public spaces and businesses too soon will lead to another wave of horror. While new cases of the Spanish flu of 1918 slightly waned by early November, the disease found new momentum only weeks after public spaces were opened the week of November 3. The curve wasn't flattened and sustained in 1918, leading to a deadly W pattern of the disease. 'Spanish flu' Hindsight Though leaders, news reporters, and residents referred to the virus as a "grip" or influenza "epidemic," history tells us it was in reality a pandemic of the H1N1 strain of viral pneumonia, with symptoms much like those brought on by infection by the COVID-19 strain of viral pneumonia. The assumption among scientists and doctors in 1918 was that the Spanish flu was caused by the spread of a bacterium. Scientists reacted accordingly and released a bacteria-killing serum to be administered via inoculation. The virus, which was too small to be detected by the microscopes of the day, could not be destroyed and was not contained, thereby infecting an estimated 500 million people around the world, or one third of the world's population. It killed an estimated 50 million people. Lives lost in the United States amounted to close to 700,000. One theory published in 2004 asserts that the virus originated at a military camp in Haskell County, Kansas, in the spring of 1918, after soldiers set fire to a large mound of manure, expelling billows of toxic smoke into the air. Scores of soldiers died of pneumonia weeks later. However, other scientists uncovered and analyzed reports of a mysterious and deadly respiratory affliction in Europe as early as 1917. We know from history that the first brutal wave of the disease struck in the United States on its East Coast in early September 1918, beginning in Boston, where soldiers on furlough arrived by ship from Europe. Children under 5-years old and adults over age 65 are normally the most vulnerable to succumbing to harsh flu symptoms. Yet, in 1918, a high mortality rate among healthy adults from the late-teen years to mid-30s baffled heath care leaders and scientists. The casualty rate among soldiers on furlough supported the notion that the the virus spread via soldiers returning home, a narrative that fed a larger political debate of whether America's sons should have been in the European fight at all. The flu hit hard during the fall of 1918, then waned, then reappeared, then waned, then reappeared. This W curve baffled doctors and scientists, as well as community leaders, who reopened public gathering places when the worst of the epidemic had seemed to pass. In 2018, scientist Michael Worobey explained this W-curve and the high mortality rate among the young. Immune systems are usually able to battle viruses first encountered in childhood. In 1889, the spread of an H3N8 virus caused a pandemic — the so-called "Russian" or "French" grip/flu. Young adults in 1918 would not have been exposed and therefore had not developed an immune response. And the fact that children fared better in surviving the 1918 flu outbreak suggests that less deadly flu viruses of the same strain were in the air several years prior to 1918. Other scientists attribute the high fatality rate among young adults to their strong immune system, which sends cytokine proteins to build inflammation to protect an attacking virus. The resulting inflammation in the victims' lungs— as a natural guard against a rapidly multiplying virus -- led to the fatal increase of fluid in the lungs. In 2018, the CDC embedded this statement in an article on its website about the 1918 influenza pandemic: "Since 1918, the world has experienced three additional pandemics, in 1957, 1968, and most recently in 2009. These subsequent pandemics were less severe and caused considerably lower mortality rates than the 1918 pandemic. The 1957 H2N2 pandemic and the 1968 H3N2 pandemic each resulted in an estimated 1 million global deaths, while the 2009 H1N1 pandemic resulted in fewer than 0.3 million deaths in its first year. This perhaps begs the question of whether a high severity pandemic on the scale of 1918 could occur in modern times. "Many experts think so. ..." Unfortunately, Trump and many in his administration, as well as his supporting media pundits, did not agree, dismissing the potential deadliness of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 for American residents throughout January, February, and part of March 2020, as the disease found its initial victims in the United States. Residents didn't hear much from President Woodrow Wilson about the influenza pandemic in 1918, as he was at capacity as Commander-in-Chief of American troops fighting in Europe during the final weeks of the Great War. He also was immersed in Fourteen Points-based peace talks with world leaders. However, U.S. Congress passed an emergency million-dollar package for funding scientists to come up with a vaccine. Of course, not knowing the disease was caused from a virus, science failed to protect the population from this deadly flu. As Reported by the Detroit Free Press I searched the Detroit Free Press (Freep) database (remotely from home) at the Detroit Public Library for news articles about the 1918 "Spanish" flu pandemic written in October and November 1918. Like what we’re experiencing today, schools and businesses were closed, concerts and sporting events cancelled. Medical workers worked to exhaustion. Controversy brewed about the spread, risk, and graveness of the disease. Health officials and government leaders disagreed about whom to quarantine and what to close and when and how. To appreciate how harsh things for Detroit's flu victims in 1918, it's critical to understand what life in Detroit was like in 1918. The United States was at war. People were grieving the deaths of young men in Europe. Residents were coping with wartime rationing of goods and fuel. When the influenza pandemic hit the home front, politicians did not discuss a stimulus package of money given directly to citizens.

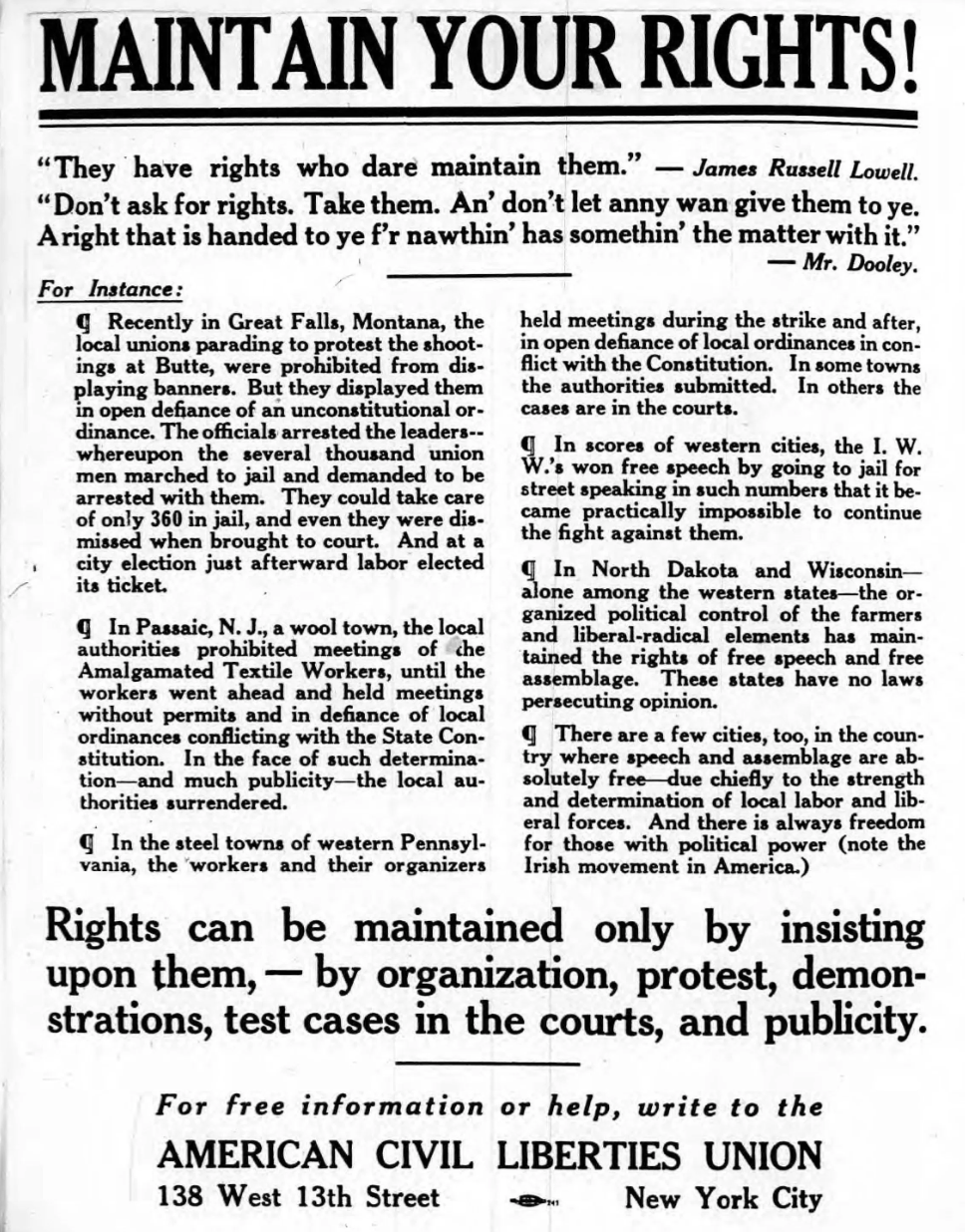

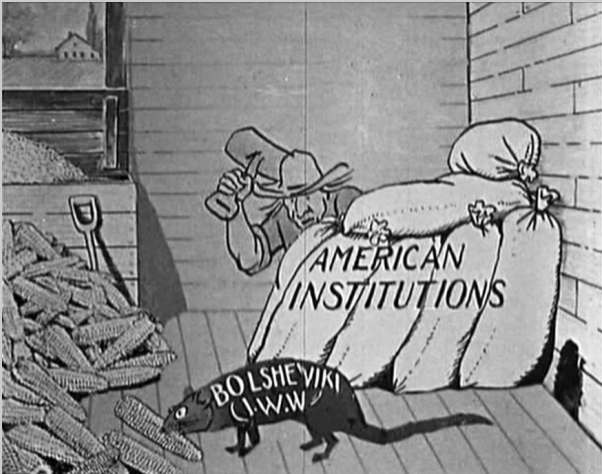

America’s First Amendment guardians in 1920

What I loved then and now about The United States is exactly this — the healthy pluralism of such encounters as mine on the campus of WSU, the right to have these conversations openly, the rights of leftists, and all of us, to gather and hand out literature. The First Amendment protects these rights. And our First Amendment watchdog is the ACLU, the organization born of the National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB), which was organized in 1917 to defend Great War (World War I) protestors and conscientious objectors. Founding members rebranded the mission in 1920 in response to the Palmer raids, viewing the activities of the DoJ as countering founding principles of the United States and in direct violation of the US Constitution, specifically the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights. The ACLU’s founding members, per its first meeting minutes January 19, 1920, included Roger Baldwin, Crystal Eastman, Helen Keller, Walter Nelles, Morris Ernst, Albert DeSilver, Arthur Garfield Hays, Jane Addams, Felix Frankfurter, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, and Rose Schneidman. A hundred years later, the ACLU’s work has benefitted us all across the political spectrum. I can’t help but believe that if it weren’t for the ACLU, the Wayne States leftists I encountered 30 years ago would not have been permitted to discuss their views with me openly. Chances are I might have been persecuted for having studied and traveled in communist countries. Events in the United States — in Detroit — a hundred years ago illustrate how injustice strikes communities without the safeguarding of our First Amendment rights

Preparing for Prohibition

Late 1919, local authorities and residents were gearing up for the Volstead Act to go into effect January 1, 2020. Though the prohibition of alcohol for consumption had gone into effect in Michigan in May 1917, Detroiters enjoyed a supply from neighboring Ohio. With the Volstead Act drying up all U.S. states, Detroit’s bootleggers turned to a supply chain from Canada. And many of Detroit's doctors had been writing prescriptions for whiskey, which would be filled in Windsor pharmacies just across the Detroit River. The Canadian government had announced on December 10, 1919 that it would lift its war-time prohibition on alcohol (and horse-racing) effective January 16, 2020 and granted amnesty to offenders who were criminalized while the act had been in effect. The manufacturing of liquor would be permitted for shipment from one province to the other. This restricted the sale of intoxicants, but opened up the means, per export permit, for Detroit's neighbors in Windsor to have liquor delivered to their homes for “private consumption.” We know from history that bootleggers, like the Purple Gang, took advantage of this policy to illegally transport Canadian whiskey from Windsor over the Detroit River and Lake St. Clair into Detroit, the Downriver communities and St. Clair Shores. So in 1919, while bootlegging opportunists like the Purple Gang were setting up logistics for importing bonafide Canadian whiskey, other less-sophisticated operators were selling low-grade moonshine. On December 27, 78 deaths were reported in four states (Michigan was not among them) within 48 hours from drinking “fake rum,” which was actually wood alcohol with brown coloring to pass as whiskey. Though Detroiters were spared this tragedy — still enjoying ample, though costly and illegal (but legal from a pharmacy), supply of genuine whiskey -- the move to crack down on alcohol distribution was ramping up by state and federal law enforcement. This led to a series of raids. It was difficult for Detroiters to discern from legitimate law enforcement agents from thieves. For example, the Christmas Eve edition of the Detroit Free Press reported that men posing as state food and drug enforcers seized 8 gallons of “Christmas cheer” from a Detroit man’s cellar. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed