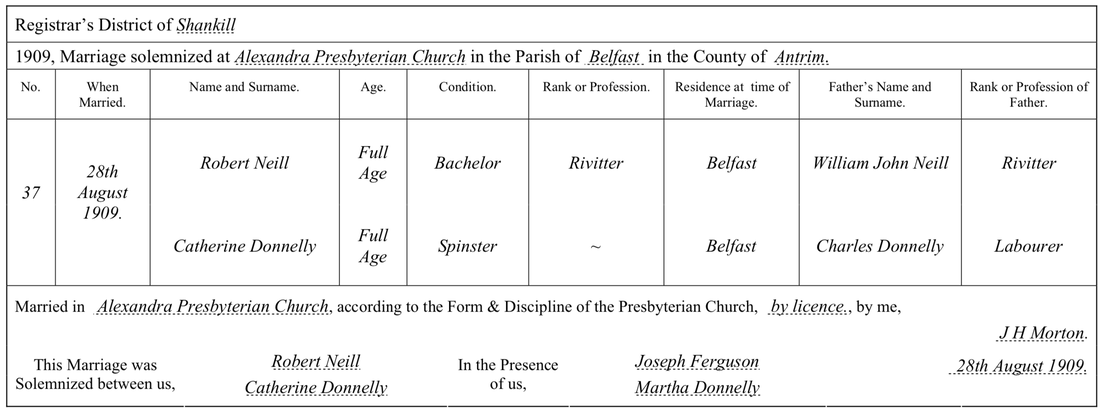

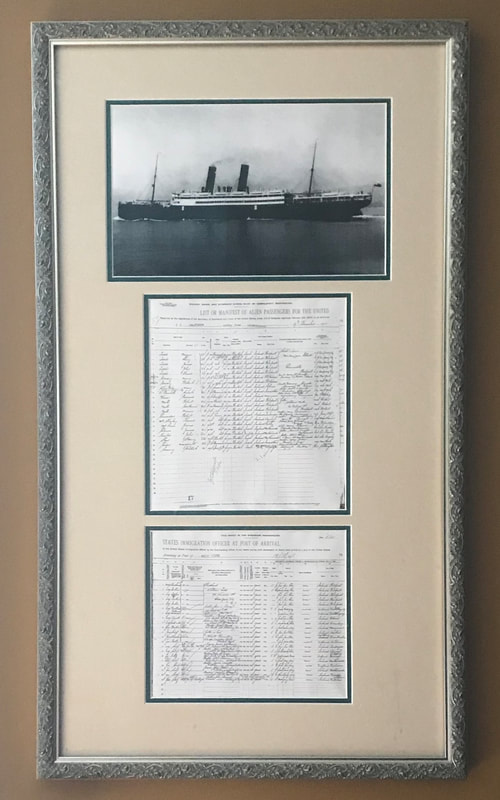

By Melissa Walsh For me, “Irish” is less adjective and more verb — a search. I dig through documents and heirlooms of my heritage like an archeologist picking and dusting to uncover buried bones and lost treasures. Seeking answers to questions I ask myself about myself, I ponder how I fell under the writer’s curse, why my preferred way to cocktail is with light sips of whiskey, why I’m drawn to songs and story fertilized with loss, and why I'm sensitive to faux affection from those unfamiliar with the misery and the miracles that are the luck of the Irish. I look past the American practice of sporting clownish green swag on St. Patrick’s Day and into the truth of Irish perseverance. This truth rings from lovely, doleful Irish song: lyrics rich with wit and rebellion, instruments booming with pride and affection. My ancestors left behind wee clues of my Irish heritage, anecdotal evidence of hardship and sorrow admitted and absorbed and also of strength gained by trial, transcendent justice won by faith, and mercy given from hope's well. I see images of ancestors fighting to survive and choosing to thrive. I remember some who were unable to believe in love or bear witness to poetry, and my family grieved their fall into despair. I recall those who landed drunk or stoned, medicating emotional wounds sustained as victims of dysfunction and injustice. Though Irish truth can be unromantic, it is spirit-filled, bringing pain to be redeemed and allowing the possibility that a loving God would permit one to endure more than they can handle alone. To thrive is to know and respond to the value of living in charitable community. True love and genuine friendship are fueled with charity, mercy, and long-suffering. We gain glimpses of beauty and strains of wisdom from pursuing love at risk and experiencing the element of joy only known while breaking bread in bona fide fellowship. Affliction experienced in living becomes growing pains — surviving love and maturing into thriving in love. W.B. Yeats wrote, “Happiness is neither virtue nor pleasure nor this thing nor that but simply growth. We are happy when we are growing.” My memories of Antrim- and Mayo-rooted trinkets and tales teach me about living and dying and loving and hating. They are traces of evidence of the truth of my heritage. The Shillelagh There was the shillelagh on the piano displayed as something decorative. I wondered about its past. Souvenir or weapon, or both? My paternal grandfather told me it was authentic, originating from his family. My grandfather's father was Michael John (certainly anglicized from Micháel Seán) Walsh (my father’s namesake), born in Ballina, County Mayo, in 1965. He immigrated to the United States with his older brother, Martin, in 1879. Martin and Michael became railroad-workers, settling in Ionia, Michigan, a town that grew with Irish railroad workers rooting themselves with opportunity to work and to feed themselves and their families. Their mother, Bridget (née Clarke) Walsh, (their father was called Michael Walsh) gave birth to 19 baby boys and girls, but only six, all sons, survived into adulthood. A younger brother, Thomas, eventually joined Martin and Michael in Ionia, Michigan. The youngest brother, John (Seán), born in Ballina in 1879, eventually immigrated to Chicago; I don't know when. Brothers Anthony and Patrick died in Ballina. Census information reveals that the Walshes of Ballina lived in Liverpool, England, during the early 1880s. By 1901, they returned to Ballina. My great grandfather married twice. He had a daughter with his first wife, Mary (née Sweeney); their baby, Geraldine, died as an infant. Mary died in 1911. In 1912, he married my great grandmother, Martha (née Loughlin), who was born in Canada to an Irish immigrant father and Quebecois mother. Michael and Martha Walsh had a daughter and two sons. My grandpa, Lawrence (also called Larry or Lonnie), the youngest, was born in 1915, the year his father turned 50. My grandpa married a girl from Ionia named Maxine (née Matthews). She was of German and Irish decent and claimed her Irish heritage as “lace curtain.” She called my grandpa’s Irish family “shanty.” My grandparents moved to Detroit, where my grandpa worked in the Grand Trunk railroad yard located about where Detroit's Renaissance Center is today. They had a daughter and two sons. My dad, the youngest, cannot recall a memory of receiving affection or discipline from his mother. He remembers his mother as a depressed and angry woman. He said that she never once told him to brush his teeth and that she was a horrible cook who cooked rarely. The kids fended for themselves for food, finding money to buy a pie or a bag of chips at a neighborhood store. When I was a girl, I spent several weekends with Grandpa Walsh and his new wife in their home in Detroit, on Manistique near Mack, where I received lessons in Irish history, namely about how the Irish suffered under British rule. I remember listening with horror about how an Irishman could be put to death for fishing or for teaching or for speaking Irish. He used to say, "You're lucky to go to school. Remember that. My dad wasn't allowed to go to school. The British made it against the law for Irish children to learn to read." And I have remembered this. In Ballina, there is a short road (Walsh Street) and marker dedicated to Patrick Walsh, a Ballina rebel who was executed by the British in 1798 for his role in the Irish Rebellion. I wonder if this Patrick Walsh was a brother or a cousin of my great, great grandfather, Michael Walsh, who was father to my great grandfather Michael Walsh, or maybe better said, my father Michael Walsh's great grandfather, Michael Walsh. So many Michael Walshes in my ancestry. In addition, my brother is also a Michael Walsh. I wanted to name my oldest son Michael, but his father said, "There are too many Michaels in your family." So I had to settle with giving him the middle name Michael. But I don't think you could possibly have too many Michaels. It's a beautiful name. The Fighting My grandmother left the family and moved back to Ionia when my dad was 15-years old, not long after the family had relocated from their flat on Seminole near Warren to the middle-class edge of the city near Kelly and Eight Mile. My grandma died when I was a tot. I'm told she met me a few times. My dad told me that when he and his brother were little boys, they ran away from home, believing that this would force their parents to realize their love for their sons and give them the parental affection they craved. The police found the young brothers and took them to the station. When my grandpa arrived, he beat my dad and uncle with a rubber hose, while the police observed. My dad said this was the worst beating of his life, which was less severe than what my uncle received. You see, my grandpa had beat my uncle first and tired himself before beating my dad. My dad and his older brother were the tough guys in their new neighborhood and at Denby High School in 1960. My dad said the only fight he started also was the only one he lost. Catholicism My dad told me my grandpa took his three children to church. “He dropped us off on his way to the bar,” my dad said. “My brother and I walked in the front door and out the back and went to the pool hall. That was ‘going to church’ for us.” When I was a kid, my parents started attending a protestant church. My grandpa was furious. He accused my dad of having joined a cult. I remember Grandpa's friendly way when he was happy. He liked to strike up a conversation with me about Peanuts cartoons. He smelled of whiskey when he bent down to greet me with a kiss. His face was always rough with stubble. On the infrequent occasions when my mom invited him over, he always arrived with a bottle of whiskey. My mom would roll her eyes and put it in the liquor cupboard, unopened. I served myself from this stash of whiskey during my high school years. Hope and Memory have one daughter and her name is Art, and she has built her dwelling far from the desperate field where men hang out their garments upon forked boughs to be banners of battle. O beloved daughter of Hope and Memory, be with me for a while. The Coat of Arms When I was a teen, my mom discovered a company that sold swag sporting the Walsh coat of arms. She ordered sweatshirts and glasses with the image. Once or twice a year, I wear my green sweatshirt with the Walsh coat of arms, sometimes underneath one of the Irish sweaters my mom made me. According to their Coat of Arms, the Walshes were fighters. The arrow-pierced swan denotes the motto: Transfixus sed non mortuus, or “Transfixed (pierced), but not dead.” The red chevron references notable enterprise colored by martyrdom. The green arrows represent strength and steadfast readiness for battle. And there’s the knight’s helmet under the swan’s feet. Today, Walsh is the fourth-most common surname in Ireland, according to stats posted on the “Ireland Before You Die” website. The Walsh clan is first known to have arrived in Ireland during the 1172 Anglo-Norman invasion. The name means “Welshman,” or foreigner. Like the Irish, the Welsh are Celtic. Yet, history brings tales of Walshes being treated as British by the Irish and as Irish by the British. The Chest In my childhood home, next to the piano was an old chest used by my maternal great grandparents and grandmother when they emigrated from Belfast. They arrived at Ellis Island aboard the S.S. California in December 1911. My great grandfather worked in a Belfast Shipyard. I have the certificate my great grandfather, whom I called “Papa,” received in November 1911 for completing a five-year apprenticeship as a riveter for Workman & Clark Company, or "the wee yard." This was next to the "grand yard," or Harland & Wolff, where the RMS Titanic was built. My grandma often spoke about how she toured the Titanic with her father and mother before the great ship moved from Belfast to Southampton. She knew this because her parents told her so. She was a baby at the time. Her father also told her that he had worked on the Titanic and that he had submitted a request for trans-Atlantic passage aboard the ill-fated ship for the family of three. Who knows? He spun a great many yarns. But I can verify the family's passage on the SS California, because I have the ship's manifest. Today, my mom stores afghans in the old chest that once carried the belongings of my grandma and her parents to Ellis Island. Lines from New York stopped in Detroit at the Michigan Central Railroad Depot (the former depot on Jefferson and Third, which was torn down in 1966). I imagine my great grandmother’s brother Billy (five years senior) awaiting their arrival at the building and my great grandmother, Catherine (née) Donnelly carrying my grandma, then a tot, and my great-grandfather, Robert Neill, carrying the chest. (I learned that my great grandmother's given name was Kathleen and anglicized to Catherine. She went by Katie, but I called her "Mama.") The knitted goods my mom keeps in that old chest were made with the craftsmanship that continues in the female line of my Belfast heritage. Like my mom, grandma, and great grandmother, I began knitting as a little girl. I became a lapsed knitter during the years of raising my four sons, however. There was no time to be the mom I yearned to be for them as I tackled breadwinner role. I did much for my sons, but knitting Irish sweaters for them fell away. They each have sweaters made by my mom. I expect to knit again in a few years with my flock having flown my nest. The knitting craft remains in me, like my fondness for poetry and bagpipes and shortbread. The end of art is peace.  My great grandparents' marriage certificate. My great grandfather was a year younger than my great grandmother. My grandma said that an aunt on the Neill side told her that when the pair were engaged, the chatter in their mixed Roman Catholic/Protestant neighborhood led with, "Did you hear? Wee Bobby Neill is to be married." The Manifest During my visit to the research center on Ellis Island in 2009, I learned my grandma and her parents arrived in the United States on the S.S. California from Derry on December 9, 1911. My great grandfather, great grandmother and grandma are shown as passengers sponsored by my great grandmother's father, Charles Donnelly (shown on a 1901 Belfast census as having been born in Derry and noted as unable to read and write) on 479 Congress Street in Detroit. My great grandmother's older brother, Billy, had been the first to immigrate to Detroit. He found steel work on Zug Island. And he married the landlady from whom he rented a room. Then he sent for his father and siblings, including my great grandmother. Three of the siblings died from tuberculosis a not long after immigrating — Agnes, 25; Charlie, 20; and Minnie, 18. The manifest also shows "the closest relative from whence" as William Neill, my great grandfather's father (a protestant), who would remain in Belfast with my great grandmother, caring for young children, including the baby, Sammy, who was born in 1910. My great grandfather was one of 12 children. My grandma is described on the manifest as Minnie Neill, age 9 months. The age is incorrect; she was born May 30, 1910, nine months and two days after her parents were married (August 28, 1909). My grandma told me she hated the name Minnie since she was a little girl. When she was 5-years old, she demanded to be called Mae. And as Mae she was known until she died on November 12, 1997. After arriving in Detroit, the family of three spent several weeks living with Billy and his wife, Laura, on Elmwood between Fort and Lafayette. After my great grandfather got a job driving a street car on Fort Street, they moved to a flat on 731 E. Fort Street, between McDougall and Elmwood. My great grandfather went to night school to earn a high school diploma, after which he landed a manager job working for Ford Motor Company. The family then moved to 1444 Hibbard Street. Not only did the Neill family of now four -- my great aunt was born June 15, 1913 — move to Hibbard, but so did several Neill and Donnelly siblings and cousins. Between Kercheval and Jefferson, Hibbard became a new mixed Belfast neighborhood in Detroit — the Donnelly clan alongside the Neill clan. My great grandmother had nine siblings. She and six of her siblings were born in Glasgow, Scotland, where her father had work. Later, the family returned to Belfast. Here three youngest siblings were born there. A 1901 Belfast census lists her occupation as "Doffing Yern." She was 13 years old then. Her older sisters' occupations were "Spreding Yern" and "Year Realer." Her older brothers were laborers, like their da. I recall as a child hearing about my great grandma having worked in a textile mill before immigrating to Detroit. The census showed me the facts. My mom and grandma told me that my great grandmother was outspoken in her opposition to religion. And she did not attend church or pray at mealtime. However, my mom told me that when she was a little girl spending the night at her grandparents, her grandmother, my great grandmother, clandestinely led her in bedtime prayer, kneeling next to the bed and crossing herself in the sign of the Trinity. Katie Donnelly was a lapsed Catholic, but, just as I’m a lapsed knitter, it remained in her. My great grandfather arrived in Detroit a lapsed Presbyterian. My grandma told me that, though her parents were married in a Presbyterian church in old Belfast, they did not attend church in Detroit. As my great grandmother decried religion, however, my great grandfather in later years embraced the ugly politics of religion. My grandma told me he joined a local Detroit Orangemen order, enraging her mother and her. “But he was a philanderer and they did not get on well anyway,” I remember my grandma telling me when I was a teenager. I asked, "What's a philanderer?" The Stories I have few memories of my great grandparents. I do remember their accents, how they called me “wee little Missy.” I recall my great grandmother as smiling and loud and wearing a loose house dress. My great grandfather was quiet and stone-faced. I am told they each suffered from dementia when I was a little girl. I conclude my great grandmother’s was a merrier strain of the condition. My mom, grandma, and great aunt told me many stories about my great grandmother’s wild and rebellious ways. She was an active suffragette soon after arriving in Detroit, up until women gained the right to vote in 1919, even though she herself was not a U.S. citizen and could not vote. I was told she “burned her bra before her time.” She never wore a bra … not ever. My great grandmother also was a working mom, beginning with cleaning homes of the wealthy in Detroit’s Indian Village before working for Parke Davis for three decades. She also made whiskey during prohibition, malting barley in the bathtub in their home on Hibbard Street. My mom said, when she was a girl in the 1950s, she remembers her grandmother serving whiskey to guests, rolling up the rug in the living room, and blasting Irish tunes with her mouth organ, inspiring all in the house to dance. My mom told me a story, which, she said, illustrated the kind of marital relationship my great grandparents had. When she was a little girl, she went with her grandparents out to “the country,” which would be suburban Detroit today, to get farm eggs. On the way home, with several dozen eggs in the car’s trunk, my great grandmother continually nagged my great grandfather to drive carefully. “You’ll crack the eggs, Bobby.” she kept saying. As soon as they arrived home, my great grandfather stomped out from the car and straight to the trunk. He lifted each carton of eggs and slammed it down on the alley, yelling, “There you are, Katie, I cracked the eggs, like you were saying I have.” Everything we do matters. Our lives are sacred. There are no small players. There are no small tasks.” The Stew and Scones I grew up knowing Irish stew as mutton and potato stew, not corned beef and cabbage. My grandma told me corned beef is English, not Irish. She also showed me how to make Irish scones, which are fried on low heat, not baked as English scones are. We pronounce them as [scawnz], not [scoanz]. My son Conor loved helping make scones when he was a little boy. It started with a school project requiring him to bring in a food representing his heritage. When I make scones today, I think of my grandma and I think of Conor during the process of cutting the butter into the flour, kneading the mixture into a thick dough, and shaping it into triangle-shaped biscuits, which I fry slowly over 280º heat. The Linens

When my grandma died, my mom gave me a box of decorative and touristy linen pieces. They came from the linen mills of Belfast, sent to my great grandmother by relatives there. I knew my great grandmother worked in a linen mill as a child. I knew this was awful. I knew that the Belfast mills were prone to catch fire and that those fires were deadly to many mothers and children working in said mills. How did it feel for Katie Donnelly to receive novelty Belfast linen? When she opened a package from her homeland and saw linens, did she feel sad? Proud? Wee Memories, Hopes “Look, I wanted to be an individual but my ma wouldn’t let me,” says the character Erin in Derry Girls. I’m a writer, not by choice. I am cursed with the psyche and disposition of a writer. My great aunt Martha — my grandmother’s sister — called me “odd.” Frequently. My grandma, an avid reader, would wink at me and whisper, “Don’t listen to her, Missy. You’re fine.” When I die, my sons will inherit notebooks full of manuscripts and poems I’ve written over many years. Maybe they'll publish some; I hope they'll read them. I didn’t write for publication as much as for curiosity and self-therapy. I haven’t had the will to seek a market for most of it. As I grow older and hungrier and more confident, I send bits out into the abyss of on-spec publishing — wee scribblings of my view of the world and my discoveries, hopes, strengths, insights, heart-aches, and hang-ups. I find few people in my world who will listen, but maybe one day my work will find readers who want to listen. This writing is simply my loving tribute to my ancestors.

1 Comment

My friend's cousin, Mike, went as Jesus. And all were amazed.

Jesus is standing next to me at the bar waiting for a drink. I just received my whiskey on the rocks.

He's wearing a white gown with red sash and sporting a headband made of twigs delicately wrapped with small flashing red lights. He has dark longish hair and a full beard. He appears to be in his thirties. A beardless man wearing a Santa suit approaches, announcing, "Hey, Jesus. I'm going to order a water. Will you hook me up?" Jesus laughs, eyes twinkling, as the bartender hands him his order. "If you don't," the guy wearing the Santa suit warns, waving his finger, "I'm going to toss the water out on the floor and make you walk on it!" I laugh with Jesus. He shoots me a wink and holds up a shot glass of clear liquid as if to make a toast. "Happy birthday, Jesus." Socializing with a tangible Jesus spun my beliefs into collisions in my mind -- common sense battling religious guilt.

Published in Grosse Pointe News Aug.16, 2018.

By Melissa Walsh

Traveling port to port in my family’s powerboat filled my childhood summers. And still today, in my 50s, I prefer being on water than on land in summer. So I have a powerboat and also sail with friends. I find the most joy in sailing, a passion I share with my boyfriend. Over dinner Saturday, my dad, curious about our love for sailing, shared an observation from his 50-plus years of power boating around the Great Lakes. “We would see a group of sailboats leave port early in the morning,” he recalled. “Then after spending the day in port, we’d take off for the next port about 4 (p.m.). And sometimes we’d see the same group of sailboats coming into port late that night! I never understood why they’d want to give up the whole day just getting there.” “Because it’s about the boat ride,” my boyfriend said. “They love the boat ride.” I thought of a piece of art my oldest son made when he was 4 years old at Grosse Pointe Nursery School. It’s an 8 1/2-by-11-inch sheet of paper with pasted pieces of construction paper on it depicting a sailboat in rough water. A teacher wrote my son’s name — Shane — at the top with this Bible verse: “I will be with you always …” Matthew 28:20b. Shane made this little masterpiece in fall 2001. I framed it and have kept it next to my bed all these years. It ministered to me while raising my four sons through rough and still waters, fierce and favorable winds, with me alone at the helm. Reading this small piece of scripture through my American lenses, for a long time I perceived it to mean God will be with ME — Melissa, struggling single mom — always. However, the translation, using plural “you,” means God will be with me IN COMMUNITY always. Few sail single-handed. Most sail in community. Though powering through the current and chop of Lake St. Clair from point A to point B can be fun, it does not render the same working-together community required for the “good sail.” The powerboat captain looks straight ahead, his passengers behind him holding on to something when the boat hits white-capped waves. The engine runs too loudly to have a conversation. Open beers get spilled. Yet the forces of Mother Nature are overpowered by the fiberglass hull pushed by ample horsepower. With sailing, a community of skipper and crew works together beating close to the wind to reach their destination. Crew members feed the skipper information about puffs coming and boats about to cross while he or she steers from the helm calling tack. The power of the lake is respected and the skipper is minded while crew members cooperate to find that awesome groove sailors love. Then confidently set on course cruising to port with the sails trimmed and sheets cleated, the sailors can relax, enjoying the boat ride. They chat. They have a meal. They sit in awe of God’s beautiful world all around them. And sailors like me feel that promise: God is with us. If honor is a force in history transcending any sense of entitlement Americans perceive as rights to comfort and greed, then America may win a few meaningless battles against those seeking asylum here only to lose the war to virtue.

By Melissa Walsh

Missing in our nation, top down, is the notion that bad behavior is permeable in community. Bad behavior spreads through attitude and policy like yeast in dough or like a cold virus in a workplace. Good behavior also spreads, despite and countering unethical laws and rules. The civil rights movement is an example of good behavior spread by brave, committed people, who gave up safety and comfort for collective honor. During the centuries of slavery, Quakers and other courageous abolitionists illegally, but morally, aided fugitive slaves. A good person is more concerned about right relationship with others than legal prohibitions countering compassion. “Whole people see and create wholeness wherever they go; split people see and create splits in everything and everybody,” wrote Franciscan friar Richard Rohr in his book Falling Upward. If we were a whole nation, we would welcome desperate families teeming our borders. But we are a split nation — split well beyond partisanship and disputing the very cause of America. Are we a nation of comfortable individualists or a nation valuing reason, charity and justice with the aim of collective honor? “Whole” people lost to “split” people in Nazi Germany. So did those in Sarajevo during the early 1990s, where I attended university in the late 1980s. I was eyewitness to the early infection of the virus of hate contaminating former Yugoslavia. I’m witnessing the same strain of virus here in the United States, as citizens and political leaders feel encouraged to blame the weakest among us shamelessly, detached from personal moral accountability and collective honor. So in recent weeks we’ve received reports about detention centers holding children taken by our government from parents fleeing to safety from the instability in Central and South America. We’ve heard from detention center workers that they are forbidden to comfort distressed children as young as those still in diapers. We witness nefarious policy defended by the U.S. Attorney General with irrelevant biblical references. Why would our Justice Department support attacks waged against the tired, poor, huddled masses yearning to breathe free? If honor is a force in history transcending any sense of entitlement Americans perceive as rights to comfort and greed, then America may win a few meaningless battles against those seeking asylum here only to lose the war to virtue. History will reflect the truth of this president, who views socio-politics as one big real estate “deal” and holds children in detention as collateral to gain leverage on a border-wall vision. Deplorable is not harsh enough a term to describe this warped sense of political maneuvering. Political players applying a moral compass, such as former first lady Laura Bush, are speaking out. But if other good citizens are silent, there will be more harsh treatment of the most vulnerable among us by this administration and more blemishes in American history. Meanwhile, imprisoned children remain detained, barred from human comfort and from even knowing the welfare of their parents. They suffer and wait with the view of a sign with Donald Trump’s image and a quote, “Sometimes by losing a battle you find a new way to win the war.” Another vainglorious leader in history said it this way, “Arbeit macht frei.”

By Melissa Walsh

During the long road trip back from a lacrosse tournament recently, my 16-year old son and I were chatting about hockey. We were talking about how much we love playing hockey. Before he began playing lacrosse, he had been a hockey guy. He still is — a goalie. All four of my sons have been on skates since age three. I didn’t start lacing ‘em up until much later in life. Me: “When you guys were little and I hadn’t started playing yet, I wondered if you ever got tired of playing hockey. I also wondered if the pros got sick of being on the ice so much. But now I get it. You don’t get tired of it. I could play hockey every day and be very happy.” My son: “Really, you could? I think I could play every day, too.” Me: “You know why I could play every day and love it.” My son: “Why?” Me: “Because when I play hockey, I’m completely away from all of the stress and problems of my life. One hundred percent. It is the one activity I do when I absolutely do not think of any of my problems and worries at all. Not on the ice. Not on the bench. Not in the room with my team mates.” My son: “Yeah. Me, too.” Me: “That’s what makes playing hockey so important.” Then I encouraged my son to keep playing hockey throughout his life. College. Beer leagues. Whatever. “As long as playing hockey is in your life, you won’t get old,” I told him. “It’s the fountain of youth.” My son nodded. I continued to drive on thinking about what I had just said about what playing hockey means for me in my life. Isn’t that how the game should feel for kids, too? Completely worry-free. Problem-free. Pure joy and all fun all the time — on the ice, on the bench, in the room. When parents make the youth hockey game about youth performance and not the pure fun of competing as part of a youth team, they’re introducing problems into the experience of playing hockey that would not develop organically among the kids. Even at “elite” youth hockey levels, the hockey game should always feel as pure as shinny with friends on a remote pond away from critical adult eyes and commentary. Always. This is to play the game “loose,” to play it creatively and dynamically; it’s playing for the love of the game and a healthy will to win. Glass-banging and critical commentary screamed through the glass taint the game with anxiety and insecurity streamed into the minds of the players. And wise youth hockey onlookers know that good hockey demands confidence among the players. In youth hockey coaching clinics, we coaches learn about how to let the game teach us. We watch our players play the game the way they know to play it in the moment; accordingly, we note what to teach or emphasize during the next practice. Game time is usually not the right time for overt instruction from coach … and never the right time from parents at the glass; the game is doing the teaching. Players win or they learn. This is why you will see many good youth coaches watching silently. During practices, these good youth coaches teach like crazy; they instruct, demonstrate, and engage with positive reinforcement continually, not leaning on the stick just watching. Parents should know what it is for a kid to be in the game, keeping in mind that for the players the game is the great escape into a special experience owned by the players and understanding that the game itself is the best teaching tool. So, hockey parents, don’t interfere with that. Don’t crash the players’ game experience with your will of what you desire the game to be for you. Apart from cheering for all sweet goals and all great saves, keep your mouth shut and hands down during the game. Keep the game pure and worry-free for the players. © 2015 Melissa Walsh |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed