By Melissa Walsh As I write this, leaders and healthcare workers of my home community of metro Detroit, and other communities around the nation, are faced with rising casualty counts due to the spread of the novel coronavirus COVID-19. In the past 24 hours, 1,719 new cases were reported in Michigan 78 Michiganders died, most of them in the tri-county area of metro Detroit, tallying 337 deaths. In the state, 9,334 people are infected. The virus is in the air, as is fear. Now we can imagine the horror faced in the fall of 1918, when Detroit's Department of Health reported 18,066 cases of influenza between October 1 and November 20, during which 1,688 people died. The disease reemerged in December and continued throughout January 1919. Another 10,920 cases were reported by late February 1919. What's especially eery, is that Michigan's rate of increase of contraction of disease from COVID-19 infection and rate of flu-induced death in March 2020 are uncannily similar to the numbers released by the state in October 1918 due to the spread of the Spanish flu. Like today's spread of the Covid-19 flu virus, the Spanish flu virus hit hardest in the state in Detroit and its surrounding suburbs. What Detroit history of fall of 1918 teaches us is that the rescindment of closure of public spaces and businesses too soon will lead to another wave of horror. While new cases of the Spanish flu of 1918 slightly waned by early November, the disease found new momentum only weeks after public spaces were opened the week of November 3. The curve wasn't flattened and sustained in 1918, leading to a deadly W pattern of the disease. 'Spanish flu' Hindsight Though leaders, news reporters, and residents referred to the virus as a "grip" or influenza "epidemic," history tells us it was in reality a pandemic of the H1N1 strain of viral pneumonia, with symptoms much like those brought on by infection by the COVID-19 strain of viral pneumonia. The assumption among scientists and doctors in 1918 was that the Spanish flu was caused by the spread of a bacterium. Scientists reacted accordingly and released a bacteria-killing serum to be administered via inoculation. The virus, which was too small to be detected by the microscopes of the day, could not be destroyed and was not contained, thereby infecting an estimated 500 million people around the world, or one third of the world's population. It killed an estimated 50 million people. Lives lost in the United States amounted to close to 700,000. One theory published in 2004 asserts that the virus originated at a military camp in Haskell County, Kansas, in the spring of 1918, after soldiers set fire to a large mound of manure, expelling billows of toxic smoke into the air. Scores of soldiers died of pneumonia weeks later. However, other scientists uncovered and analyzed reports of a mysterious and deadly respiratory affliction in Europe as early as 1917. We know from history that the first brutal wave of the disease struck in the United States on its East Coast in early September 1918, beginning in Boston, where soldiers on furlough arrived by ship from Europe. Children under 5-years old and adults over age 65 are normally the most vulnerable to succumbing to harsh flu symptoms. Yet, in 1918, a high mortality rate among healthy adults from the late-teen years to mid-30s baffled heath care leaders and scientists. The casualty rate among soldiers on furlough supported the notion that the the virus spread via soldiers returning home, a narrative that fed a larger political debate of whether America's sons should have been in the European fight at all. The flu hit hard during the fall of 1918, then waned, then reappeared, then waned, then reappeared. This W curve baffled doctors and scientists, as well as community leaders, who reopened public gathering places when the worst of the epidemic had seemed to pass. In 2018, scientist Michael Worobey explained this W-curve and the high mortality rate among the young. Immune systems are usually able to battle viruses first encountered in childhood. In 1889, the spread of an H3N8 virus caused a pandemic — the so-called "Russian" or "French" grip/flu. Young adults in 1918 would not have been exposed and therefore had not developed an immune response. And the fact that children fared better in surviving the 1918 flu outbreak suggests that less deadly flu viruses of the same strain were in the air several years prior to 1918. Other scientists attribute the high fatality rate among young adults to their strong immune system, which sends cytokine proteins to build inflammation to protect an attacking virus. The resulting inflammation in the victims' lungs— as a natural guard against a rapidly multiplying virus -- led to the fatal increase of fluid in the lungs. In 2018, the CDC embedded this statement in an article on its website about the 1918 influenza pandemic: "Since 1918, the world has experienced three additional pandemics, in 1957, 1968, and most recently in 2009. These subsequent pandemics were less severe and caused considerably lower mortality rates than the 1918 pandemic. The 1957 H2N2 pandemic and the 1968 H3N2 pandemic each resulted in an estimated 1 million global deaths, while the 2009 H1N1 pandemic resulted in fewer than 0.3 million deaths in its first year. This perhaps begs the question of whether a high severity pandemic on the scale of 1918 could occur in modern times. "Many experts think so. ..." Unfortunately, Trump and many in his administration, as well as his supporting media pundits, did not agree, dismissing the potential deadliness of the novel coronavirus COVID-19 for American residents throughout January, February, and part of March 2020, as the disease found its initial victims in the United States. Residents didn't hear much from President Woodrow Wilson about the influenza pandemic in 1918, as he was at capacity as Commander-in-Chief of American troops fighting in Europe during the final weeks of the Great War. He also was immersed in Fourteen Points-based peace talks with world leaders. However, U.S. Congress passed an emergency million-dollar package for funding scientists to come up with a vaccine. Of course, not knowing the disease was caused from a virus, science failed to protect the population from this deadly flu. As Reported by the Detroit Free Press I searched the Detroit Free Press (Freep) database (remotely from home) at the Detroit Public Library for news articles about the 1918 "Spanish" flu pandemic written in October and November 1918. Like what we’re experiencing today, schools and businesses were closed, concerts and sporting events cancelled. Medical workers worked to exhaustion. Controversy brewed about the spread, risk, and graveness of the disease. Health officials and government leaders disagreed about whom to quarantine and what to close and when and how. To appreciate how harsh things for Detroit's flu victims in 1918, it's critical to understand what life in Detroit was like in 1918. The United States was at war. People were grieving the deaths of young men in Europe. Residents were coping with wartime rationing of goods and fuel. When the influenza pandemic hit the home front, politicians did not discuss a stimulus package of money given directly to citizens.

There was no nationally coordinated pandemic health plan (as we are experiencing today as the federal government minimized the COVID-19 threat well into March). Most critically though for flu victims in 1918, unlike today, there was no test to detect a virus, no anti-viral medication, no intensive-care support, and no mechanical ventilators. Many died within 12 hours to a few days of presenting symptoms, their lungs swelling and filling with flood as the virus rapidly replicated in their bodies.

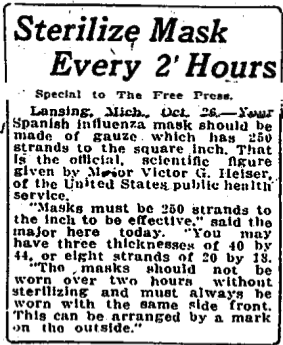

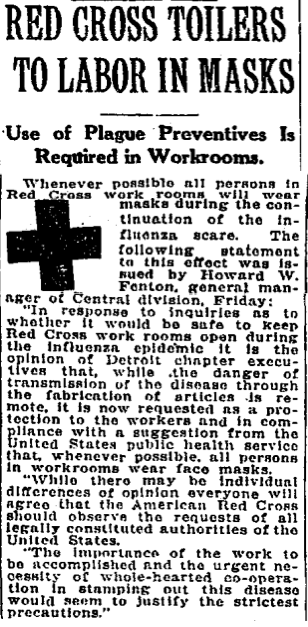

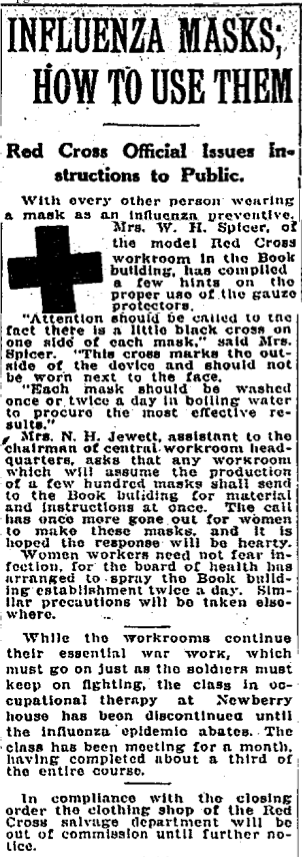

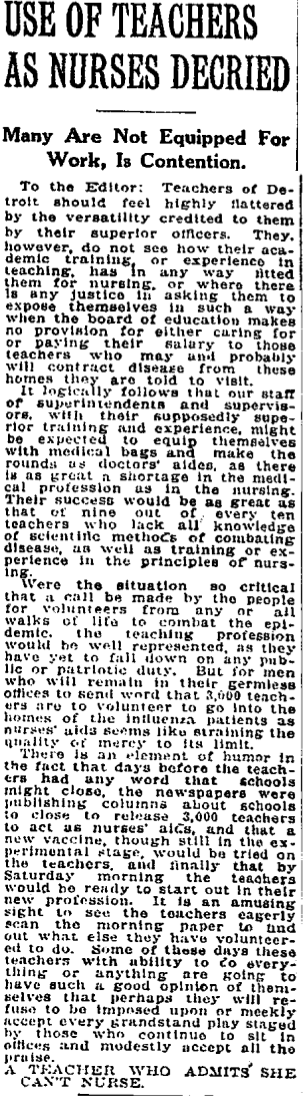

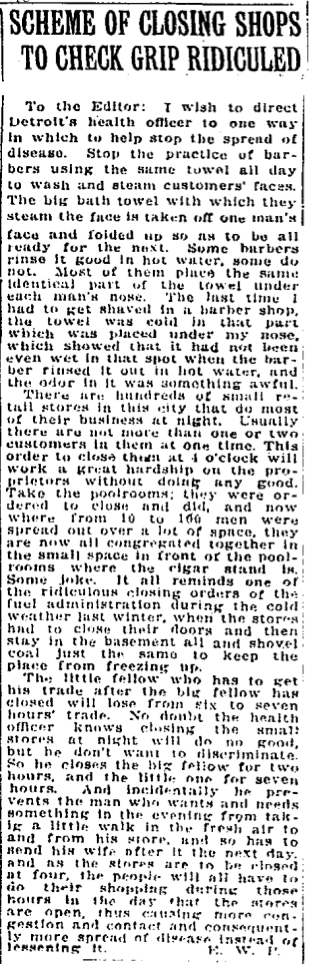

Newspapers, which were under a "voluntary" wartime censorship overseen by the U.S. Congressional Committee on Public Information (essentially a Woodrow Wilson-directed propaganda arm chaired by George Creel), were riddled with headlines and headshots of prominent individuals (the wealthy) who succumbed to the flu. Obituaries listed many more regular residents who died from the flu, alongside listings of Detroit's war dead. Editorials and letters to the editor cast blame on various leaders, organizations, or classes of people for the disease's initial outbreak in the United States and for its invisible spread. Though health mandates to stave the spread of influenza were issued and enforced by state and community leaders, Detroit wartime production pushed on. While other states and cities continued a ban on public activities, metro Detroit's leaders succumbed to public pressure and lifted the ban prematurely. For a short time, schools were closed, but teachers were mandated to volunteer to care for the ill. Only the female teachers were mandated to do so, while the male teachers were directed toward healthcare administrative support. While Detroiters today can enjoy a cocktail and movie-streaming at home during the 2020 Covid-19 outbreak, Detroiters in 1918 were prohibited from enjoying liquid merriment while enduring this pandemic, as the state had gone dry on May 1, 1917. Like today, reports from Wall Street tempted the greedy to forego caution to keep business churning its returns. “Peace talk, too, has had some effect on trade, which reflects some hesitation,” read a report in the Freep, “but some responsibility for this is credited to the country-wide epidemic of influenza, which has hampered industry, resulted in the promulgation of health regulations, the closing of the theaters and schools, and finally in restricted buying by the ultimate consumer.” Initial Reaction: Quarantine, Rumor, Debate The first deaths resulting from the flu in Detroit were recorded October 1, but it would be weeks before state and local leaders prohibited public gatherings. Twenty college football games scheduled for Saturday, October 12, were cancelled the day before. This included the Michigan-Camp Custer game. When 523 new cases appeared October 14 – the most tallied in a single day since the first case was reported in Detroit – Detroit Health Commissioner James W. Inches recommended closing public places during a meeting with the Wayne County Medical Society. “Dr. Inches endorsed the statements of several other doctors at the meeting, including Dr. William Donald, that most of the influenza in Detroit is nothing more or less than the French grip which became prevalent in this country in 1889," reported the Freep. "However, the virulent type, which has as its most peculiar symptoms a suffusion of the face, nosebleed and inflammation of the larynx, is rapidly spiking, reports received at the health office in the last few days indicate, Dr. Inches said. This is the type that is taking so heavy a toll of life in the east.” Dr. Donald, who had recently returned from Boston, where he investigated the conditions of influenza patients, believed Detroit would fare better, saying, “We have their mistakes to guide us.” The first population restricted in Detroit was that of military men from leaving military housing downriver and at other camps in the region. The Freep reported on October 13 that 63 soldiers at Camp Custer in Battle Creek died between October 11 at 7 p.m. to October 12 Saturday morning from pneumonia induced by the influenza epidemic. More than 1,000 were hospitalized with pneumonia with another more than 4,000 patients battling less acute flu symptoms. Nearly 300 died since early October. Also, on October 13, the U.S. War Department reported 864 dying in military camps in a single day – October 12. It reported a total of reported cases since September 13 as 234,868 and total death over the same period as 9,199. The Freep reported on October 16 that “several medical officers will be tried by court-martial” for “infraction of quarantine rules,” by allowing officers and enlisted men with flu symptoms convalesce at their civilian homes. The article also dispelled rumors that the medical officers charged were to be executed at the camp. The article concluded with listing the 40 who had died in the camp during the previous two days. The state of Michigan reported 1,502 new influenza cases during the same time period, and 50 dead due to flu-induced symptoms. On October 16, the University of Detroit and University of Michigan released senior students trained in the medical field to serve community health needs. This spurred debate among health officials – those who insisted that all students should remain in quarantine and those who argued that the communities required the help of additional medical personnel. The same day, the Freep reported another 41 dead and 1,821 new cases in Michigan, outside Detroit and Grand Rapids. Inches issued a quarantine of all soldiers and sailors “to keep men on furlough from infected military and naval establishments out of the city.” Within only days of shutting dance halls down, Inches was under pressure to reopen them. The October 18 edition of the Freep led by quoting Inches: "I don't expect that the crest in the Spanish influenza epidemic will be reached in Detroit for at least another week." Just a day earlier, 823 new cases were reported and an estimated 31 deaths. This was now the highest number of new cases in a single day recorded since the epidemic first surfaced in Detroit. Nonetheless, according to the Freep, "He (Inches) will meet with a committee of dance hall proprietors Friday (the following) morning, and, if they agree to advertise precautionary measures in their places, carefully disinfect their halls nightly and bar people sneezing and coughing, he will remove the ban." The same article reported that Grace Hospital had barred all visitors and "it is expected that the other hospitals of the city will act likewise within a day or so." Mandates from Lansing At 11:30 p.m. on Octobers 18, Michigan Governor Albert E. Sleeper ordered all Michigan "non-essential" institutions and businesses closed, including theaters, movies, churches, lodges, political functions, and others. Workers in Detroit's munition plants were considered "essential war work." With the church closings, local newspapers were asked to print scripture lessons and sermons in Sunday editions. The official mandate from the governor's office read: "Whereas, it is a matter of common knowledge that the state of Michigan, in common with other states of the union, is facing the serious and imminent danger of an epidemic from the disease commonly known as Spanish influenza, which is prevalent in practically all communities throughout the state; "and, whereas, said disease is highly contagious and is spread by personal contact with the persons infected therewith thus creating the necessity of avoiding insofar as is possible, all gatherings and meetings whatsoever. "Now, therefore by virtue of the authority vested in me as governor of the state, I hereby direct that all churches, theaters, moving picture shows, poolrooms, billiard rooms, lodge rooms and dance halls shall be and remain closed until further proclamation. And that all unnecessary public meetings or gatherings be avoided. "All health officers and health boards in the various cities, villages and townships of the state shall take such action as is required by law to carry out and insure the careful performance of the terms and conditions hereof. "In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the great seal of state to be affixed at Lansing, this 19th day of October 1918. Signed by Governor Sleeper" The governor's next move was to order masks immediately following the release of the mandate. The state permitted the closing of schools to be left to the discretion of community leaders. Dr. Andrew P. Biddle, a member of the state health board and Detroit schools board, declared Detroit schools would not close. An October 19 Freep article quoted Biddle: "If you close, you close everything. If you close your theaters, you should close the churches; if you close the churches, you should close all places where people congregate. If you close all of these, you must close your streetcars, and if you shut off the streetcars, you will paralyze the city of Detroit. "We think in Detroit that it is unwise to close. We base that opinion on figures we have received from cities of our size where the closing order has been in effect. None of them can show where the closing has done any good. We have made use of the theaters as a means of education and propose to do so with the churches, but we think it would be unwise to close." On October 19, 1,890 new influenza cases were reported in the state and 71 deaths due to the disease. Nationally, 14,153 died, amid reports of "the disease subsiding rapidly in camps" and that "the height of the epidemic among civilians has been reached." At midnight October 20, all Michigan non-essential business and organizations closed "for an indefinite period." The Freep reported 344 new cases and 12 deaths on October 20, in addition to a vaccine (a "serum to inoculate") being considered by Dr. Inches for factory and healthcare workers. The vaccine, which had been developed in Chicago, was sent to Detroit's Parke-Davis laboratories for testing. As for the effect of closings in Detroit, the Freep reported, "Downtown streets were practically deserted all day, for there were no amusement places for anyone to go to. Persons lucky enough to possess autos were able to enjoy about the only form of recreation possible and as it was the first Sunday in six weeks that motoring has not been taboo because of the ban on use of gasoline; the roads were filled with cars." Reported in the same article: "The Red Cross workroom in the Book building was a busy place. Hundreds of face masks were being made for use by persons coming in contact with influenza sufferers and persons who might be infected." Dr. Inches issued a call to "all women who have had any experience and have any knowledge in the care of the sick" to volunteer with the Red Cross. According to the article, Dr. Inches viewed the increased chance of volunteers becoming sick as minimal, that they were "as likely to become infected in their own homes." The efforts to contain the disease were "in the hope that it will be possible to show the state authorities such results in blocking the malady's spread in the city that the ban on all places where people can congregate will be lifted by the end of the week at least." On Monday, October 21, new cases tallied at 1,112 and 56 more died. Dr. Inches mandated all schools closed and directed teachers to move from the classroom to the hospitals as healthcare aids "to make possible a more vigorous and efficient campaign against the malady than is in effect now and probably accomplish result that would cause the lifting of the state ban on churches, theaters and all other public meeting places by the end of a week or 10 days." On October 22, the state issued a mandate that all retail stores close at 4 p.m. each day for disinfecting. The state also suspended all outdoor activities indefinitely. Yet streetcars continued to run and became packed with commuters at 4 p.m.

Profiteering

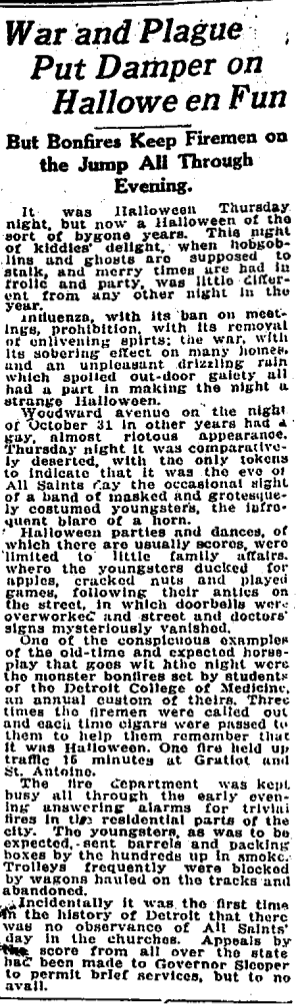

The randomness of the invisible killer in the air forced desperation. People sought home remedies and concoctions marketed to ward off disease, inviting the hoarding of ingredients and marked-up resale. An October 25 Freep article led with this: "Several sharp-witted, lily-handed gentlemen in New York, known as drug brokers, have made a pretty penny out of the influenza epidemic that weeks ago began its country-wide sweep in the eastern states. "In part, their fortunes are based on the superstition of a large proportion of the American public — firm belief that camphor or asafetida, worn in a bag about the neck, will frighten away disease germs, especially the influenza bug." The papers also reported the hoarding and resale of food staples, such as butter, eggs, sugar, and other wartime rationed goods. Reopening public places On October 27, the Freep reported that Inches will propose to Governor Sleeper that Detroit schools and other public institutions can safely reopen as early as Wednesday, October 30. Citing a drop in new cases 615 new cases on October 26), Inches said, "I'm convinced we've passed the crest of the epidemic. So the need of having the emergency force of teachers, which today began spreading educational propaganda, is really over. Our regular nurses can handle the situation as it is now." Rather than attributing the decrease in new cases of the disease to closures containing its spread, Detroit's health commissioner declared the worst of the health crisis had passed. Though new cases were declining, the daily death rate continued to rise. Eighty-three Detroiters died from the flu on October 26. Critics of the ban of public gatherings supported Inches, mainly political opponents preparing for the November 5 elections. Governor Sleeper took exception and issued a statement on October 27. In part it read: "I don't believe that in the history of politics in Michigan, or in the whole country, for that matter there has been a more inexcusable, baseless, unfounded and disgraceful episode than this campaign to make it appear we are attempting to smother politics under the guise of fighting the most deadly epidemic we have had in Michigan for many, many years." State health officials opposed Inches' proposal to reopen institutions and businesses on October 30, urging a minimum of another two weeks of lock-down. Per the governor's order the statewide ban officially remained in place. Detroit's health department reported 548 new cases and 71 deaths on October 30. But pressured by business owners and community leaders to remove the ban in Detroit, Inches continued to appeal to state health directors and the governor, arguing that the worst in Detroit had passed. On October 31, he removed teachers from mandatory care-giving; yet he still could not gain state approval to reopen the schools. The same day, when new cases numbered 129 and deaths 79, Inches also removed the order that stores close early for disinfection. The November 3 edition of the Freep reported that Governor Sleeper was lifting the ban, a report that turned out to be false. The misunderstanding might have been due to the closing phrase in the governor's November 2 statement asking Michigan residents to be patient as the ban continues: "It may be that this will be the final Sunday on which it will be necessary to keep the churches closed and that in another week we may be able publicly, in our houses of worship, to give thanks." Inches proceeded in reopening public places in time for Election Day on Tuesday, November 5. The flu death count in Detroit on November 2 was 53 with 262 new cases. He and Mayor Marx also gave the green light to reopen the schools Monday, November 4. The ban on public gatherings was over in Detroit on Election Day, though the day saw 213 new cases and 42 deaths. Ironically, one of the Free Press news films was a public service announcement on how to keep well and avoid infection from influenza. The Nov. 6 edition of the Freep reported, "Crowds in Cadillac square watching The Free Press election returns Tuesday night rivaled those which a few weeks ago packed the forum in front of the Liberty statue in support of the Fourth Liberty loan. "The returns were flashed from a window of the Hotel Pontchartrain upon a large canvas across the front of the new Real Estate Exchange building as fast as they were received, with frequent totals to keep the crowd in touch with mass results. "Between figures, there were fine war pictures, current news films, lots of comedy and a good scenario or two. Whimsical sketches, such as a jug illustrating the wet vote in Ohio, were merrily received by the crowd." Spontaneous crowds emerged again in Detroit on November 11 and 12 in celebration of the official end of the Great War, among a population that seemed to have forgotten the horrors of the recent, and continued, spread of a deadly strain of influenza. In December another surge of cases and deaths would come, lasting through most of February.

Detroit Free Press articles by date:

The paper did not publish bylines with these reports. “Spanish influenza deals western universities football big blow,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 12, 1918, p. 10. “Public places to be closed.” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 15, 1918, p.1. “Influenza slows pace of industry,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 12, 1918, p. 11. “63 die in camp; grip receding,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 13, 1918, p. 3. “864 die of plague in day at camps,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 14, 1918, p. 7. “6 Custer doctors face Army court,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 16, 1918, p.6 “50 dead in day’s state grip toll,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 16, 1918, p. 16. “41 die, 1,821 state grip cases in day,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 17, 1918, p. 2. “Furlough men from infected camps barred,” Detroit Free Press, Oct. 17, 1918, p. 1. "823 new cases of influenza," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 18, 1918, p.2. "State grip decree closes up Detroit," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 19, 1918, p.1. "City will obey influenza ban," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 20, 1918, p.8. "Detroit obeys influenza ban on initial day," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 21, 1918, p.1. "Schools close as influenza plague gains," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 22, 1918, p. 1. "City extends closing order," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 23, 1918, p.1. "Epidemic gains despite fight," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 24, 1918, p.1. "134 state dead, 50,000 now ill," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 24,1918, p. 9. "3,000 teachers fight epidemic," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 25, 1918, p.1. "Grip discloses pastures new to profiteer," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 25, 1918, p.1. "Plague crest perhaps past, thinks inches,"Detroit Free Press, Oct. 26, 1918, p.1. "Schools may be open again by Wednesday," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 27, 1918, p.1. "Motor Corps aids influenza fight," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 27, 1918, p.11. "Governor raps critics of ban," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 27, 1918, p.13 "No opening this week, grip edict," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 28, 1918, p.2. "End of ban sought as epidemic wanes," Detroit Free Press, Oct. 31, 1918, p.1. "Ban on stores to be removed," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 1, 1918, p.2. "To lift plague ban this week," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 3, 1918, p.1. "Free Press film flashes returns," Detroit Free Press, Nov. 6, 1918, p.1. Other Sources "1918 Pandemic (H1N1 virus)," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html "The American Influenza Epidemic of 1918-1919," University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing" https://www.influenzaarchive.org/cities/city-detroit.html# "A shot-in-the-dark email leads to a century-old family treasure — and hope of cracking a deadly flu's secret," by Helen Branswell in STAT https://www.statnews.com/2018/12/05/1918-spanish-flu-unraveling-mystery/ © 2020 Melissa Walsh

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed