Twenty-nine years later, in 2018, I encountered Prague’s free-market make-over while traveling with my sons. It was stunning.

Photos by Melissa Walsh.

By Melissa Walsh

While a wave of revolution swept Eastern Europe 30 years ago, I was completing my degree in International Studies in Sarajevo and Vienna. During that time, I also traveled to Krakow and Warsaw, Poland, and to Prague, Czechoslovakia, participating in short-term study programs. This month, November 2019, as I’m compiling a memoir about my years abroad during the late 1980s, I’m consumed with nostalgia from my three visits to Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic. The first was while in transit to Poland by train in March 2019. The next was five days in Prague in April 1989. And the most recent was in July 2018, when I spent three days in Prague with two of my sons. But why is this month special? In addition to marking the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9), this month commemorates 30 years of democracy in the former Czechoslovakia (which in 1993 became the Czech Republic and Slovakia). Czechoslovakia had been a communist country since 1948. A series of reforms in the 1960s and a period of strikingly liberal revisions in 1968, known as Prague Spring, which included rolling back censorship, prompted the August 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia by troops from Warsaw Pact countries. A tight Eastern-bloc hold on Czechoslovakia remained for two decades. Czechoslovakia’s November 1989 Velvet, or Gentle, Revolution, began on November 17 with a student demonstration honoring International Students’ Day — a commemoration of the 1939 student demonstration against the Nazis, during which 1,200 Czech students were sent to concentration camps and nine were executed. The demonstration spawned additional anti-government protests over the next ten days, including a wide-reaching, nation-wide general strike on November 27. On November 28, 1989, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia announced the end of the party’s monopoly of power. Days later, the constitution was revised and the borders opened. On December 29, 1989, well-known playwright and political dissident Václav Havel became President of Czechoslovakia. The first two times I was in Czechoslovakia, in 1989, Havel was in prison.

In his memoir To the Castle and Back, Václav Havel called the 1989 revolution, described in the video below, “a drama in several acts.”

Havel had been active in advocating for liberal reform that led to the Prague Spring in 1968. With the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia the following August, his passport was seized and his plays were banned. Havel continued advocating for human rights, resulting in several arrests and a four-year imprisonment (1979-1983). By this time, Havel was recognized domestically and abroad as an important political dissident and crusader for human rights, earning him the Erasmus Prize in 1986.

Havel was sentenced to nine months in prison on February 21, after being accused and convicted of organizing a January 1989 anti-Communist demonstration, during which Charter 77 dissident activists laid flowers at the memorial of Jan Palach — the young man who burned himself alive in January 1969 in protest to the 1968 Warsaw Pact occupation of Czechoslovakia. He was released early from prison on May 17, 1989. In late March 1989, I was on a train from Vienna to Krakow, passing through Czechoslovakia. I remember my luggage being searched by police. Everyone’s was. The police also removed the ceiling panels in the train compartment and searched there. They searched everywhere. It was a tense experience. I also remember chatting with two Czechoslovakian guys about my age. I was 21.

In a journal entry dated April 7, 1989, I wrote about what the two young men told me about Havel’s arrest in January. They were pessimistic.

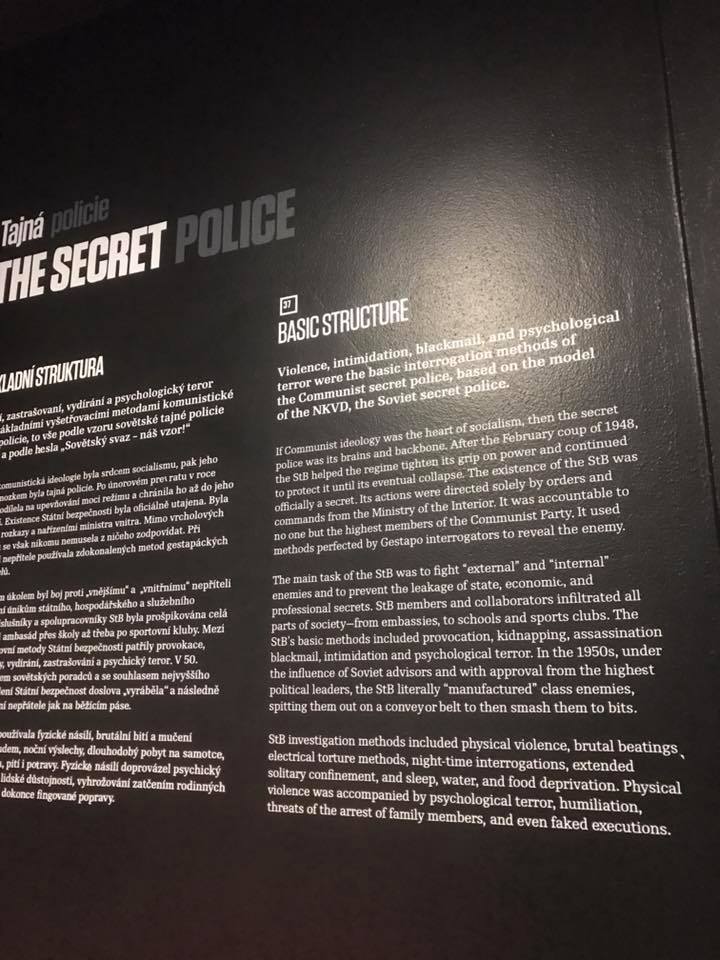

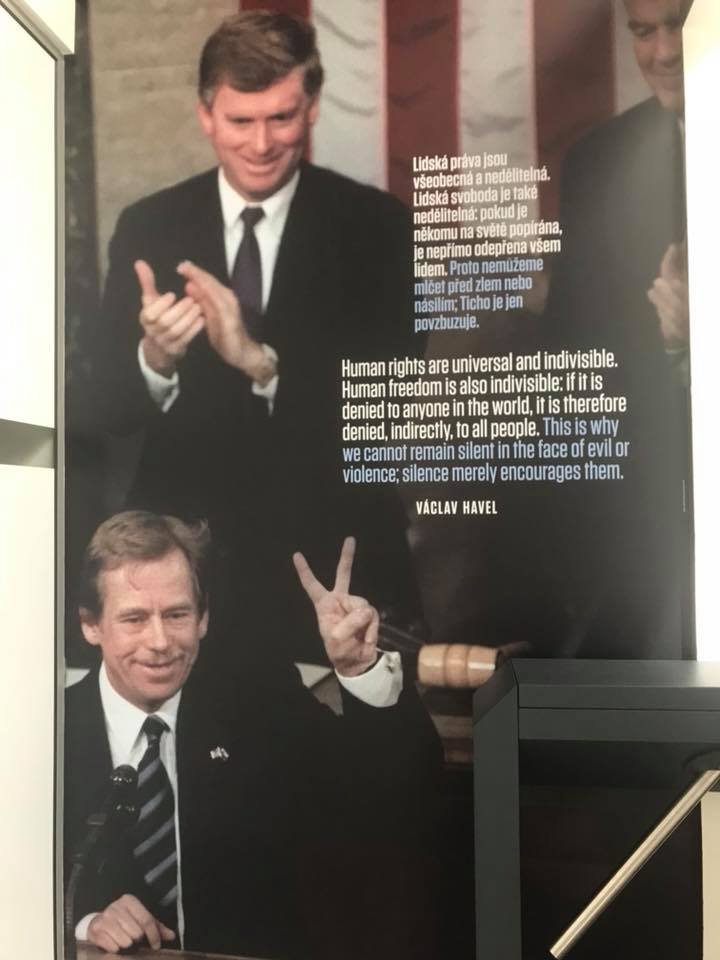

“(They) said that it’s ridiculous to pull stunts like that when there’s nothing one can do to change the situation. They have no freedom in Czechoslovakia — no Bill of Rights. It’s so hard for an American to relate to such a situation… . They were sweet guys and I wish them the best. I’ll never forget them when I think of human rights in East Europe.” During my 5-day visit to Prague in late April, I managed to speak with a few more Czechoslovakian young people, though our group from Vienna was tightly chaperoned by a government worker. They spoke to me in a whisper, nervously, about Havel’s imprisonment and desire for reform. I did not realize until later the great risk they took speaking with me — an American. Speaking with an American was viewed as suspect by Czechoslovakia’s undercover “street police." And if they were caught speaking about Havel and political reform, they would have been arrested. A week after returning to Vienna, I received a letter from one of the young men I had met while on the train to Poland — Vita. The letter was dated May 1, 1989 — the day spontaneous protests erupted during the May Day parade in Prague. The communist government made parade attendance each year compulsory. Vita lived in Bystrice — a four-hour drive from Prague. Lacking a free press, he would not have been unaware of what was happening in Prague that day. The content of that letter was bland. Certainly, Vita knew it would be screened by the party police. However, another letter from Vita dated December 10, 1989, was much different. It included this: “We have now very problems in our lives — because now is revolution in Czechoslovakia. We fight against old communist to democracy system.” He urged me to return to Czechoslovakia after some time. I’m curious to learn more about what Vita experienced during that period of radical political and economic transformation, but we stopped communicating. I don’t remember why. In our early twenties, I suppose we were just busy with work, with starting our adult lives. Havel shed light on the country's transformation that year in his memoir To the Castle and Back. Commenting on his 1989 conviction and imprisonment and the democratic momentum generating throughout the year and culminating with November’s Velvet Revolution, he wrote, “I think that this prison term merits particular notice because it reveals a lot about the events that preceded our revolution. In January of 1989, there was the twentieth anniversary of Jan Palach's suicide. The spokesmen of Charter 77 at the time were to lay flowers at the statue of St. Wenceslas, not far from where Palach set himself on fire in 1969 to protest the Soviet occupation. I decided to stand on the sidewalk and observe the ceremony on the sidelines so that if the police intervened I would be able to deliver a timely report to friends and the foreign media. The police actually did intervene, but so clumsily that it aroused the interest of passers-by and immediately mushroomed into a large spontaneous demonstration. I watched the whole thing from a distance, fascinated, although I knew that sooner or later they could arrest me. And then I walked away from Wenceslas Square to prepare my report. They arrested me on my way home and then, absurdly, found me guilty on the basis of false testimony and, as a result, the whole affair contributed considerably to the changing conditions, almost as though it had been a deliberate act of sabotage. It immediately created a huge wave of protests, not just from abroad this time, but as home as well… . “I think that more had changed in those four months than during the years of my previous incarcerations. It wasn't just because a lot had changed in the neighboring countries—in Poland, Solidarity was already having a huge influence on the communists, and in the Soviet Union there was perestroika—but mainly because Czechoslovak society had begun to awaken from the anesthesia into which it had been plunged in 1968 by the Soviet occupation.” Twenty-nine years later, in 2018, I encountered Prague’s free-market make-over while traveling with my sons. It was stunning. I captured my observations in my journal on a train from Prague to Munich: “I was shocked at the difference from when I was in Prague last, in April 1989, just days before the May Day 1989 uprising, an event that would lead to the velvet revolution lasting 10 days in November 1989. I continued in my journal remarking on the StB-driven tension I witnessed in Prague in 1989. “The plain-clothed street police were on high alert when I was there. A few young people my age dared to whisper to me, an American, about the events of Czechoslovakian politics. This was illegal, but they must have felt compelled to speak freely, though clandestinely in a soft whisper. I imagine these same people were among those in the May Day uprising and the Velvet Revolution in November. “I was able to see Prague’s amazing historic sights unhindered by crowds of tourists in ’89. So I was disappointed with my walk through stare mesto (“old town”), as it felt like a walk through Cedar Point (an amusement park in Ohio). The graffiti disappointed me, too. But the boys could see the beauty of Prague beneath the ugly capitalism, as I could see it in 1989 beneath the communist oppression. They learned a lot about both systems — the idealism and reality of both. They learned of the evils in each reality. I hope they keep this lesson in their hearts throughout their life.” My sons and I found this Havel quote displayed on an exhibit wall of Prague’s Museum of Communism: “Human rights are universal and indivisible. Human freedom is also indivisible; if it is denied to anyone in the world, it is therefore denied, indirectly, to all people. This is why we cannot remain silent in the face of evil or violence; silence merely encourages them.” Here, Havel sounds much like Thomas Paine — the great political writer who arguably contributed the most intellectually to America’s 1776 revolution that overturned the despotic rule of Great Britain. After all, it was Paine who coined the phrase United States of America. And it was Paine who committed the treasonous act of writing Common Sense — before Thomas Jefferson had written the treasonous Declaration of Independence and before anyone had treasonously signed it. Havel was Czechoslovakia’s Thomas Paine.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed