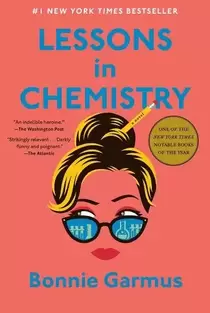

A referee refused to shake my hand years ago while I was at the bench watching a youth hockey team warming up before a game. I was the team's head coach. I was wearing a coach's jacket. The players were little girls. He saw me and skated over. "No moms behind the bench," he said as I extended my hand. I thought he had come over to greet me with the customary ref-coach pre-game handshake. "I'm not their mom. I'm their coach," I said. He asked me to show him my USA Hockey Coaching Education Program (CEP) card to prove this to him. I got my wallet out and showed it. "Well, you know, I just don't need a mom over here screaming." "I am not their mom. And I don't scream." A bit later, he brought the scoresheet over and asked one my assistant coaches, a player's dad, to sign it. I took it. "I'll sign that." I returned the sheet to the ref. He gave me a nasty look, likely returning my nasty look at him, and skated off. I remember feeling so angry during that game. So frustrated with being treated unfairly. We were playing a boys' team and won that game. We won all but one game against the boys that season. It was the girls' teams we struggled to beat. We only won two games against them. But the win-loss record wasn't the point for my 8U hockey players. Their lessons in hockey were about so much more — how to jump out onto the ice when it's scary, how to skate as fast as you can to gain control of a loose puck, how to get up after getting knocked down, especially when an opposing player had rammed into you on purpose and the ref didn't even call a penalty. For me, the coaching experience became more lessons in standing up tall and keeping my mind in check after being hit with misogynic cheap shots. To be treated with a lack of respect and not as a thinking and feeling human being stings. It hurts. It can erode confidence and surface feelings of despair and defeat. How does a woman heal from this kind of treatment? Bonnie Garmus' novel Lessons in Chemistry is a lovely story about a highly intelligent woman finding her strength and not losing her mind while being knocked down hard — like from a two-hander slash — by old school, late 1950s and early 1960s misogyny. Women Can Be Chauvinist Pigs, Too

When the novel's protaganist, Elizabeth Zott, Chemist, is ejected from her lab, Garmus shows us how she thrives after landing in a kitchen, applying common sense, scholarship, and good old moxie. Life is complicated. And kitchens can be discovery stations, we learn. What sets this story into real life is how Garmus so brilliantly brings to life complicated characters: men who do bad things, men who do good things, women who do bad things, women who do good things. (Bashing men with the proverbial sweeping hockey stick is shallow and as unjust as any other form of discrimination.) As I read a particular scene about the female HR secretary at Elizabeth Zott's place of employment, I recalled a time when I overheard two women in a rink lobby chatting about a hot topic in the news: pending legislation that would promote equal pay for equal work. "You know, I really don't care if I get paid less than a man, especially if he has a family," one of the woman said to the other. "Yeah, my husband has to carry our health insurance; so the premium comes out of his check. It's not taken out of my check. I don't care either," the other said. Enter me, unsolicited and highly perturbed. "So what if your husband dies or walks out, then would you want equal pay?" I asked the women. "Well, I just mean that usually the man pays for everything," one said. "I don't have a man paying for anything," I said. "And I'm raising sons into men. So what about me? You think I should be paid less than a man?" They stared at the floor. Awkward! "You should really start supporting women," I added. "You never know when you'll need to support yourself and your kids." I walked away. This was the only conversation I had with these women all season. They were moms of boys on my twin sons' team. But they were rarely at the rink, because their husbands did the hockey chauffeuring and, I'm sure, the ice-bill paying. Garmus' protagonist, Elizabeth Zott, has similar encounters with weak-thinking women, whose words were like punches to the gut when she was down. Why Don't You Take the Meeting Notes? The dumbest encounters Elizabeth Zott experiences are with weak-thinking men, like when men presume she's a secretary, blind to the fact that she sports a lab coat. And yes, I know what that feels like. I've endured that stupidity many times during my more than three decades as a professional. Here's one instance: When I was a logistics engineer, I was invited to a meeting by a group of technical writers, all men. They wanted me to take an issue they were having with a design to engineering for resolution. Although I was their target audience for the meeting, one of the tech writers asked, "Hey, Melissa, would you mind taking the notes for us?" "Why should I take the notes?" I asked. "Because you're probably better at it than us," another tech writer said. "Why would I be better at taking the notes?" I asked. "Well, you know." "I know what?" Silence. I asked again, "So why is it that you think I should take the notes at YOUR meeting?" No response. One of the tech writers got out a pen and pad of paper and started the meeting. No Head-of-Household Pay for You At the risk of introducing a spoiler, Elizabeth Zott falls victim to the "you're worthy of being a parent, but not worthy of a living wage" nonsense of her era. I'm witness to the residue from this nonsensical thinking that continued spreading like mildew well into the nineties and this century. I was bringing home the bacon for a family of five, which was at least 25 to 35 percent less bacon than what men were bringing home after performing the same work. A common practice then was, and maybe still is, giving a woman a title like "specialist" or "coordinator" and then loading her with genuine project management duties. This way, she could be paid less while doing the work of men holding the title "project manager." When I was working for an automotive aftermarket tool and diagnostics provider as a marketing "specialist," I traveled for work at least once a month. I never used being a single mom of four as an excuse not to travel. Not once! I wrote business cases with ROI, negotiated SLAs, wrote tool-installation guidelines, traveled out of state to meet with mechanics to promote new essential tools they were about to be required by their dealerships to purchase, traveled to California to meet with clients, etc. I felt that I even worked harder than many of my male counterparts doing the same work. I didn't leave work early afternoon to play golf, and I didn't do the two-martini lunch. Oh, and I also went to night school taking automotive technology courses so that I would understand well the work our tool endusers did. I felt it was time to approach my director and request an appropriate title with "manager" in it. He asked me why. I listed the activities I managed and said that I deserved more pay. "Well, aren't you a second income anyway?" he asked. After lifting my jaw off from my chest, I said, "Uh, no. I'm the head of a household." "Well, you get child support, right?" "A drop in the bucket compared to what I pay in childcare, not that it's any of your business." He gave me no new title, but a very small raise. I remained underpaid. I was laid off about nine months later when the tool program that I worked so hard to help launch launched. HAVE We Come a Long Way, Baby? So I have my gripes about experiencing unfair treatment because I'm a woman. I suppose that I was never savvy enough to reap the benefits I see other women getting: diamond ring, house, car, getting to hold their babies longer before returning to work. My life has made me familiar with all the liabilities of being a women. But these struggles cultivated in me wisdom, empathy, and strength of mind. There's hurt and anger in me, too, I admit. But I'm working on healing from it. Lessons in Chemistry is about all of that — the growth of a quirky and intelligent woman healing from being treated as if she were a mindless utility. From what I see in the workplace today, it seems that things are improving for women. Are they? I'm asking the younger women reading this. The millennials and gen-Zers. Tell me how things are for you. But first, read Lessons in Chemistry and learn about what we've been fighting for all these years. "Whenever you start doubting yourself, whenever you feel afraid, just remember. Courage is the root of change and change is what we're chemically designed to do." ~ from Lessons in Chemistry © 2023 Melissa Walsh

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed