All I knew was that no one in Sarajevo or from Sarajevo was sleeping well.

By Melissa Walsh

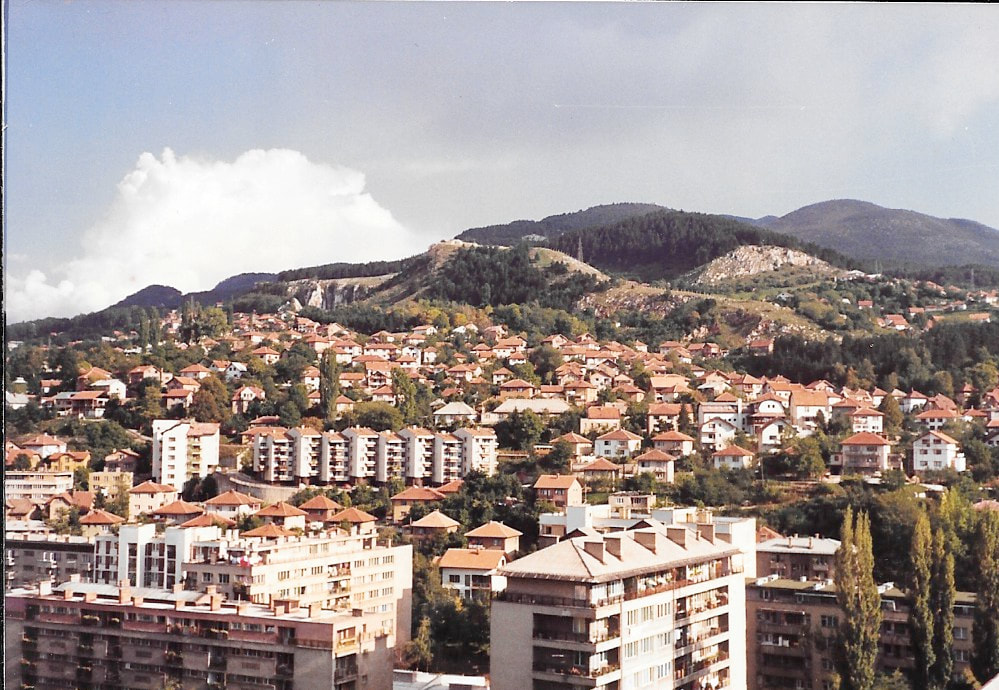

Last night I dreamt there was a large snake in my house. It looked poisonous, dangerous, until I noticed a gentle look in its eyes. I felt a maternal empathy for it. “It’s not harming me,” I thought. “I’ll let it live in peace.” My German Shepherd then lunged and attacked it. I fled the suffering, feeling powerless to save the creature from the jaws of my dog. When I re-entered the room, I saw no sign of the snake. I looked under furniture expecting a gory mess of pieces of snake butchered by my dog. I found nothing. Then I realized my dog also was missing. I woke up, relieved that it was a bad dream. At the same time, I was grateful for sleep. I suffer too many sleepless nights. When I lived in Sarajevo more than 30 years ago, I remember hearing women chatting, whom I guessed to be in their fifties, the age I am now. They would greet each other each morning with queries about sleep. Dobro jutro. Da li si dobro spavala? “Good morning. Did you sleep well?” (They did not ask, “How are you?” as American women commonly do.) Oh. Nisam. “Oh. No, I did not.” Then a statement followed explaining why. Moj sin ne moźe naći posao. “My son can’t find work.” Or Imam bolove u kolenu. “My knee hurts.” A conversation about the problems the women faced affecting their sleep continued onto the streetcar. Bosnian novelist and 1961 Nobel Prize winner Ivo Andrić wrote about sleeplessness in several of his diary entries, which he published as Signs by the Roadside. “The night is our world, and sleeplessness is our faith, our homeland and our bread,” Andrić wrote. “We do not know, hear or see one another, but we share the same dwelling, without name or form, somewhere half way between the world of the living and the world of the dead, both equally close and equally distant, so that they cannot be summoned, glimpsed or comprehended. “We are not attached by anything except the fact that we are not attached to either the world of the living, or the sleeping, or the dead, or between ourselves. Without number, shape, name, relations, bonds or laws, we are nothing but suffering, nothing but the desire not to suffer, and to resist if we have to suffer. “And sleep or waking scatter us and obliterate us forever, as though we were a mysterious, rare game of light and darkness which no one has seen and which has not known itself, but which is reborn every night.” Andrić, who was born in Austro-Hungarian-occupied Bosnia, in a village near Travnik, in 1892 lived through two world wars. He was a student in Sarajevo and a member of Mlada Bosna, the “Young Bosnia” student movement, in 1914, when fellow member of Mlada Bosna, Gavrilo Princip, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie. Andrić was arrested, but not convicted. He spent the duration of the First World War in prison or under house arrest. During World War II, Andrić wrote the novel The Bridge on the Drina, a popular work in his cannon of fiction and essays that earned him Nobel Prize distinction 16 years later. It’s no wonder Andrić wrote about sleeplessness. He was an intellectual caught up in politics that led to the death of his class mates as a young man. He was witness to occupation by a foreign power and to civil war — costly and deadly to countless innocents. For him and his contemporaries in Yugoslavia, nightmares became the truth of day. “The slightest and vaguest of all states, sleeplessness, has the firmest, double foundation,” Andrić wrote in his diary. “And a person who no longer has the strength to stay awake or the possibility of falling asleep is not saved from any of the misfortunes that can befall him. So he lies and fades away like a corpse without a shroud and at the same time he seeks answers to all the questions which life poses and with which it persecutes us. He has nothing, anywhere, but he feels his blood, love, strength and possessions steadily draining away from him with every moment.” Yugoslavia’s failing economy affected the sleep, even if indirectly, of these women I encountered at the streetcar stop in Sarajevo during the late 1980s. According to Susan Woodward in her heavily researched book about the political and economic factors leading to the disintegration of Yugoslavia, Balkan Tragedy, Bosnia, and most of Yugoslavia, suffered a rate of more than 20 percent unemployment. Close to 60 percent of those seeking work were adults under age 25. In a nation that valued higher education, offering it gratuitously to its residents, more than 38 percent of Yugoslavs under 25 were unemployed from the mid- through late 1980s. During those years, to repay national debt, Yugoslavia's politically conservative central government imposed rigid austerity federal policies, including increasing exports and limiting imports. Much of the population experienced a decrease in wages, coupled with soaring inflation. Political liberals sought reform by means of economic autonomy for the republics, which morphed into ethnic nationalism. What the West viewed and applauded in Yugoslavia as progressive reform towards a market-driven economy and democracy was tragically misunderstood.

What used to be known as the Serbo-Croatian language is now Serbian, Croatian, or Bosnian, which are linguistically the same language with variation in dialect. The word narod means both “nation” and “folk.” Therefore, when politicians spoke at rallies I witnessed there in person or on television in 1988 and 1989, calling for national independence, the interpretation by some hearers was a call for ethnic independence and territorial exclusivity and by others a call for regional community and multi-ethic unity. The interpretation by the hearer depended upon how radicalized politically he or she had become by unemployment and sky-rocketing inflation and to what degree the hearer was despairing over his or her financial prospects under Yugoslavia's strong central government, which annually rotated the head of federal leadership (the League of Communists) by republican representation, as well as how fed up the hearer had become with the promise in Yugoslavia’s 1974 Constitution of politically equitable sharing of a common Yugoslav economic pie.

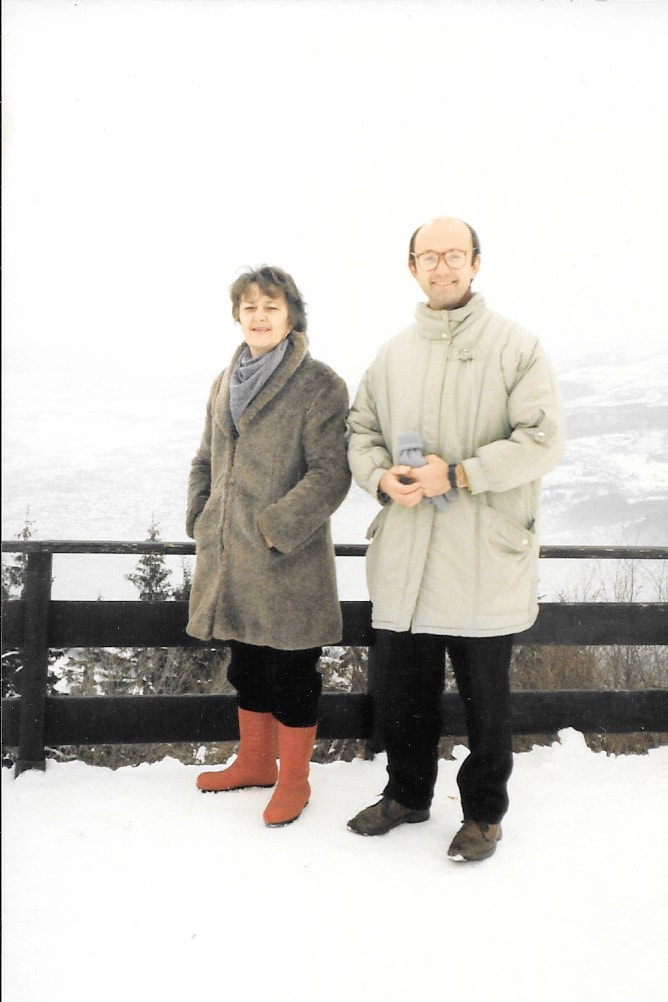

Narodni rallies further radicalized the radicals. And in mid-1991, as the Yugoslav National Army combatted Croatia's move to secede and Serbs and Croats fought for ownership of territory in Croatia that they had previously shared in community, Sarajevans believed their multi-ethnic city, the tightly integrated capital of the most diverse republic in Yugoslavia, would remain peaceful. I was told this by friends in Sarajevo in their letters. (I left in 1989.) However, in March 1992, when the question of Bosnia-Herzegovina succession from Yugoslavia was put to a vote, Radovan Karadzić, representing a radical faction of Bosnian Serbs, boycotted the vote and declared a Bosnian Serb Republic, setting up Serb armed irregulars, who called themselves Četnik. The siege of Sarajevo began April 6, 1992, when 14 innocent Sarajevan civilians were killed by snipers hiding in the upper floors of the Holiday Inn. Among the six arrested in the hotel that day for these murders was Karadzić’s personal body guard. When I had traveled in Yugoslavia by train and bus from 1987 to 1989, I periodically heard chatter among fellow passengers that I found both troubling and absurd. I witnessed radicalized youth and foolish old men calling themselves Ustaša, if Croatian, and Četnik, if Serbian. They claimed they were rebels ready to kill their perceived ethnic enemies to preserve their narod. I never heard hate speech in Sarajevo. In her memoir about covering the Bosnian war while staying in an old residential area of Sarajevo, Logavina Street: Life and Death in a Sarajevo Neighborhood, journalist Barbara Demick, said she discovered that Sarajevans were caught off-guard by the war. “No wonder, then, that Americans were baffled by the Bosnian war. So were Bosnians,” Demick wrote. “The conflict was commonly defined as ‘ethnic warfare,’ yet everyone comes from the same ethnic stock. The difference among people is primarily in the religions they practice, yet to explain the fighting as a ‘religious war’ would be equally misleading, since most Yugoslavs were not religious people.” I was back in the United States then looking to return to Yugoslavia by way of a Fulbright Scholarship for graduate study in linguistics at the University of Novi Sad. I was granted the invitation, but it was cancelled a few months later — zbog rata, “because of war.” With a mixed population, communities in Vojvodina were under threat by extreme nationalist factions. My letters from Sarajevo were returned following the start of the siege, also with a note that included the phrase zbog rata. I wondered if my friends were among the thousands dead, the thousands imprisoned, the thousands being raped, or the thousands wandering and seeking refuge. I wondered about the Sarajevans I had seen daily at the university, the market, post office, streetcar. I wondered about the kids shown in the above image. All I knew was that no one in Sarajevo or from Sarajevo was sleeping well. “A man drowns in sleeplessness as in an ocean of dense, quivering darkness,” Andrić wrote, “and he is linked by only a breath like a slender thread to the white invisible world. “I do not sleep; I suffer, but I breathe.” Each breath is a gift. How difficult would it be to sleep knowing that your next breath might be your last, your hope and right to continue breathing extinguished by a sniper’s bullet or mortar fired from the hills of your valley? “Foreigners in Sarajevo urged one another to ‘be careful,’ Demick wrote, “but the Sarajevans were more likely to say, ‘Be lucky.’” For 30 years, the anxiety of wondering who among my friends in Sarajevo were unlucky keeps me awake some nights, as does the piercing in my heart over the past three years whenever I hear American radicals scapegoating and demonizing those they perceive as the other.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed