Every human generation has its own illusions with regard to civilizations; some believe they are taking part in its upsurge, others that they are witnesses of its extinction. In fact, it always both flames and smolders and is extinguished, according to the place and angle of views.

By Melissa Walsh

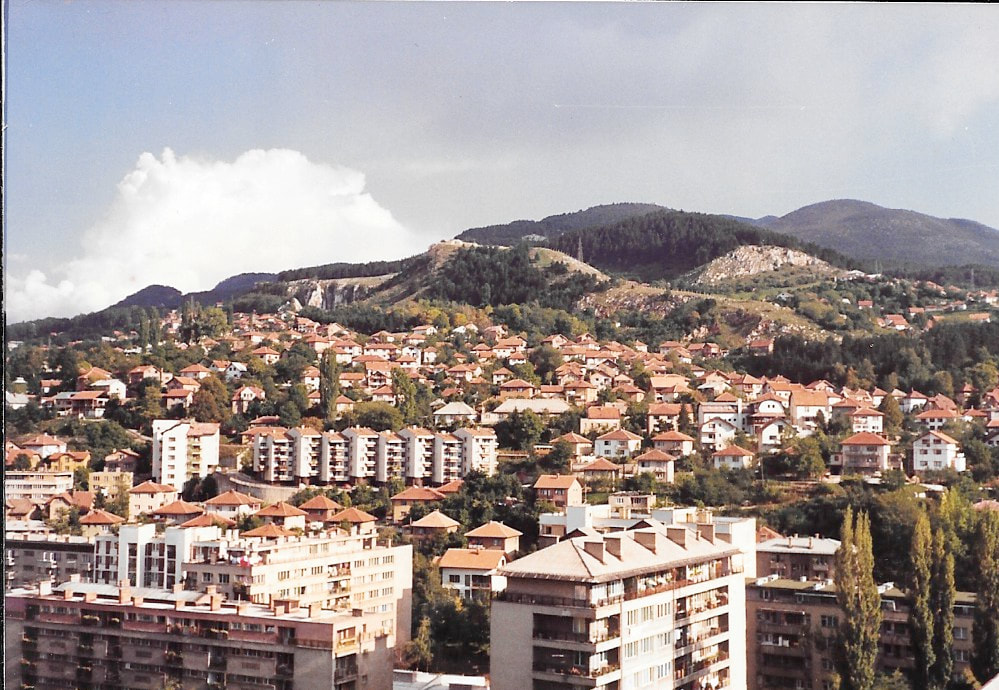

Burek and baklava. Giant juicy black grapes and luscious red tomatoes. Old men wearing the red fez selling Turkish coffee pots in the baščaršija, "marketplace." Olympic gold-winning champion basketball players at the cafe. Stars of Sarajevo’s popular rock band Bijelo Dugme at Obično Mijesto, or “Usual Place” — a bar in the baščaršija beloved by Sarajevo’s hipsters. And the cafe bar called Broj Jedan, or “Number One," set in a well-to-do neighborhood in the edge of the valley, where the politically well-connected lived. These are among my countless memories of Sarajevo. While I was a student at the University of Sarajevo in 1988, nearly each evening, for sure each weekend evening, I was among hundreds of young Sarajevans walking to the “meeting place” on Maršala Tita Ulica, "Marshal Tito's Street," where those in their late teens and 20-somethings greeted each other with Vozdra -- Sarajevan pig latin for “hi,” or Zdravo, “hello,” transposed. Vozdra, gde si? they’d say. Particular to Sarajevo was the pronunciation of Gde si?, or literally, “Where are you?” This was slang for "How are you doing?" Sarajevan youth did not pronounce gde with the prescribed hard g and hard d, but as a soft consonant blend. So to American ears, Gde si? sounded like the name "Jessie." When I uttered the greeting in the way of a Sarajevan youth, my friends would laugh. It was much like how I would react if a foreigner in my home town of Detroit greeted me with,” Yo, whadup doe?” Walking to or from the meeting place, one would pass soldiers buying kolaći, “sweets” for gypsy kids begging in the streets. They might take Principov Most, “Princip’s bridge” to cross the Miljacka River, where the first shot of World War I was fired. They might walk past the famous Sarajevo library or travel by street car past the yellow Holiday Inn and other modern buildings with a similar hideous and boldly modern aesthetic. I started from 127-A Lenjinova, an apartment building in the Grbavica section of Sarajevo, across the Miljacka from the University of Sarajevo’s Filosofki Falkutet, or School of Philosophy, where I was a student. I rented a room from a widow caring for her elderly mother and two grown sons who had finished university and were looking for work. My friends in the building included Nik, Milica, Bogdana, Nina, Igor, Goran, and Maja. They identified as Yugoslavs. Everyone I met in Sarajevo from 1987 to 1989 identified as a Yugoslav. I did not know that I was encountering a Sarajevan Yugoslav civilization in danger of extinction. The Sarajevo unity I witnessed was not an experiment. It was not a powder keg of hate. I experienced first-hand Sarajevo’s celebration of East and West — European- and Asian-influenced literature, music, and food. I witnessed close relationships between Sarajevan and Sarajevan, not between Croat and Serb, or Serb and Muslim, or Muslim and Croat. These relationships were caught in the anxiety of 40-percent unemployment among those under age 25, coupled with sky-rocketing inflation. The Sarajevo that I was first introduced to in 1987 and last visited in 1989 was a vibrant community of talented and well-educated individuals who identified as Yugoslavs. They were not hostile. They did not talk about their ethnic and religious family history unless I asked them about it. My circle of friends celebrated both Catholic and Orthodox Christmas, which are two weeks apart, Islam’s Ramadan, and communism’s May Day. They displayed Tito’s image somewhere in their apartment. They toasted each other with živeli, “to life,” or literally “(we) lived.” They laughed and added the Partisan toast of their parents who survived World War II, Smrt fascismo, slobodo naradu, “Death to fascism, freedom to the people.” I couldn’t foresee fascism about to attack this great valley of cultural diversity and national unity within two years. But I knew a man who saw through the illusion I believed in.

0 Comments

Twenty-nine years later, in 2018, I encountered Prague’s free-market make-over while traveling with my sons. It was stunning.

Photos by Melissa Walsh.

By Melissa Walsh

While a wave of revolution swept Eastern Europe 30 years ago, I was completing my degree in International Studies in Sarajevo and Vienna. During that time, I also traveled to Krakow and Warsaw, Poland, and to Prague, Czechoslovakia, participating in short-term study programs. This month, November 2019, as I’m compiling a memoir about my years abroad during the late 1980s, I’m consumed with nostalgia from my three visits to Czechoslovakia/Czech Republic. The first was while in transit to Poland by train in March 2019. The next was five days in Prague in April 1989. And the most recent was in July 2018, when I spent three days in Prague with two of my sons. But why is this month special? In addition to marking the 30th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall (November 9), this month commemorates 30 years of democracy in the former Czechoslovakia (which in 1993 became the Czech Republic and Slovakia). Czechoslovakia had been a communist country since 1948. A series of reforms in the 1960s and a period of strikingly liberal revisions in 1968, known as Prague Spring, which included rolling back censorship, prompted the August 1968 Soviet-led invasion of Czechoslovakia by troops from Warsaw Pact countries. A tight Eastern-bloc hold on Czechoslovakia remained for two decades. Czechoslovakia’s November 1989 Velvet, or Gentle, Revolution, began on November 17 with a student demonstration honoring International Students’ Day — a commemoration of the 1939 student demonstration against the Nazis, during which 1,200 Czech students were sent to concentration camps and nine were executed. The demonstration spawned additional anti-government protests over the next ten days, including a wide-reaching, nation-wide general strike on November 27. On November 28, 1989, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia announced the end of the party’s monopoly of power. Days later, the constitution was revised and the borders opened. On December 29, 1989, well-known playwright and political dissident Václav Havel became President of Czechoslovakia. The first two times I was in Czechoslovakia, in 1989, Havel was in prison.

In his memoir To the Castle and Back, Václav Havel called the 1989 revolution, described in the video below, “a drama in several acts.”

Havel had been active in advocating for liberal reform that led to the Prague Spring in 1968. With the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia the following August, his passport was seized and his plays were banned. Havel continued advocating for human rights, resulting in several arrests and a four-year imprisonment (1979-1983). By this time, Havel was recognized domestically and abroad as an important political dissident and crusader for human rights, earning him the Erasmus Prize in 1986.

Havel was sentenced to nine months in prison on February 21, after being accused and convicted of organizing a January 1989 anti-Communist demonstration, during which Charter 77 dissident activists laid flowers at the memorial of Jan Palach — the young man who burned himself alive in January 1969 in protest to the 1968 Warsaw Pact occupation of Czechoslovakia. He was released early from prison on May 17, 1989. In late March 1989, I was on a train from Vienna to Krakow, passing through Czechoslovakia. I remember my luggage being searched by police. Everyone’s was. The police also removed the ceiling panels in the train compartment and searched there. They searched everywhere. It was a tense experience. I also remember chatting with two Czechoslovakian guys about my age. I was 21. The snow doesn't give a soft white damn whom it touches. — E.E. Cummings By Melissa Walsh Here in Detroit, we were hit yesterday with 7 to 8 inches of snow. After work and school, we shoveled with a chase of hot chocolate. No big deal. I like winter. The only thing I find annoying when winter happens is the bombardment of whining about winter. With each snowfall, my Facebook and Twitter feeds light up with the grumbling. And these laments aren't from the folks who have a legitimate snowfall grievance -- those who are too old or sick to shovel their walk and drive. The gripes, I noticed, usually come from healthy people. And I know many of these people have gym memberships. Snowflakes. Just stop it. Enjoy the snow-shovel workout, maybe with your dog or with a kid. Toss snow on the dog. Dogs love that. Throw a snowball at the kid. Kids love that. Or listen to some tunes and get your snow-shovel groove going. Work it. Feel that winter beat. Snow is pretty. Snow is fun. Snow is glorious. It’s soft. In the light, sparkles like diamonds. Some of my fondest memories wouldn’t have happened without snow. The ski trips with friends. Tobogganing with my dad when I was little. Making snow angels on the playground. Years later, I enjoyed watching my kids build snow bunkers before waging a snowball battle. Today, I enjoy walking my dog on a quiet day while sporting my warm coat, my Habs tuque, and my comfy boots. I like hearing the snow crunching beneath my steps. I'm happy. The dog is happy. Life is good in the snow. And that’s not all snow is good for — the fun and the beauty. It’s also healthy. Yes, snow is good for our health! Snowfall means cold weather, which is good for our bodies. We burn more calories when we’re chilled. Seasonal allergies and inflammation are reduced in cold weather. Scholars have written white papers presenting evidence that we think more clearly in cold weather. (Here’s a link to one of those papers.) We sleep better in the winter. And our blood flow is more oxygenated as the body warms itself, especially during a winter work out — like working that like snow-shoveling rhythm or that winter wonderland strut with the dog. Mother Earth also benefits from an abundantly snowy winter. Snow’s “blanket effect” insulates the landscape for healthy gardens. Melting snow provides moisture for dormant plants and evergreens and replenishes the water supply. These environmental truths about snow not only benefit humans, but also outdoor animals in their natural habitat. The sunlight that snow reflects into the atmosphere helps the planet maintain a healthy solar energy balance and a regulated surface temperature. Here, where I live, in the Earth’s Northern Hemisphere, 98 percent of the planet’s snow falls. Without healthy snow fall here in the North, other areas of the planet are affected negatively due to a global "snowpack" shift. Less snowfall leads to changes in global cooling, which causes bad things happen, such as unexpected arrival of monsoons and other storms at unestimated lengths of duration. So to the people who complain about snow — those living in snowpack towns like mine: Do you really want the alternative? A lack of snow fall where you live has catastrophic consequences. Stop complaining. If you hate snow so much, then take steps to move south. But most importantly, while you're living in the snowbelt, be mindful about helping a neighbor who is too old or sick to shovel their driveway.

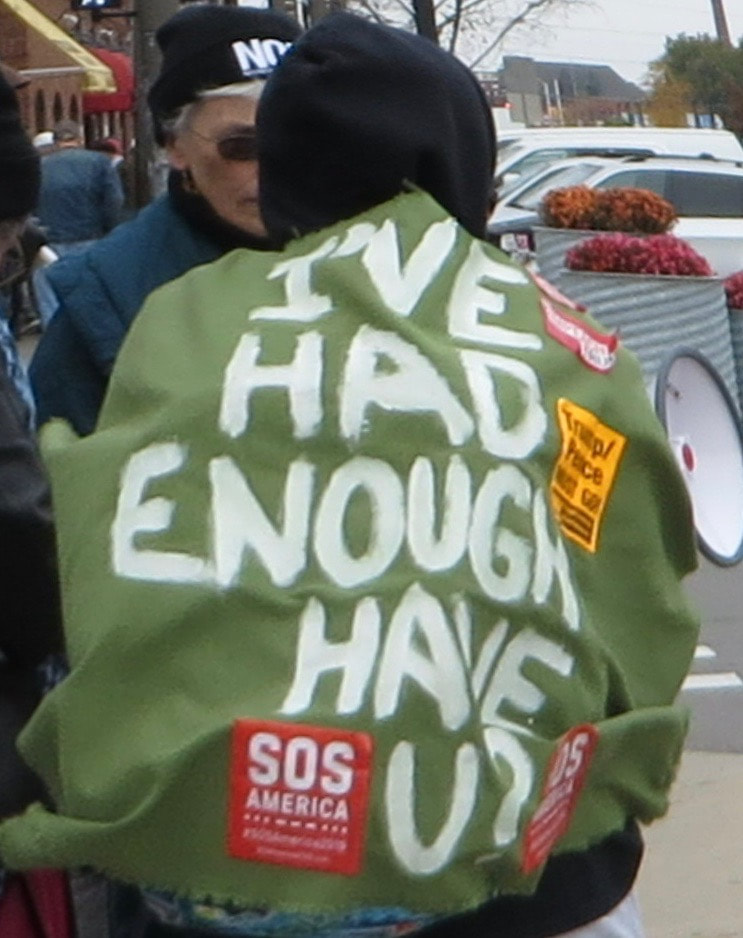

What Detroit #OUTNOW Volunteers SayCindy saysI think the unique thing here is that this is fascism. It’s not just the white supremacy and the misogyny and the imperial wars. Those aren’t new, but it’s actually a whole different kind of qualitatively more draconian rule that you’re talking about under fascism. The fact that (Trump’s) talking about treason and civil war for people who raise the hand that we’re raising, or even just impeachment, which is actually a legal process, it’s a more concentrated, I think, more dangerous time…. We have to deal with it as such. It can happen here. It is happening here. — Cindy Luiz Vicki saysThe rhetoric -- the misogynist, homophobic, xenophobic — the attacks on muslims and all the rhetoric around immigrants from south of the border, the going after your political opponents with ‘Lock her up,’ threatening to imprison people, who even from the most mainstream disagree with you, the calling of the media ‘fake news,’ those are all warning signs of fascism. They’re all signposts. Kathy saysIt’s not just what’s being done to our country; it’s also what’s not being done to protect us. Margaret saysTo me the most important thing about what’s going on right now is that we build community, because, if we don’t get everyone together, we’re not going to make it through any of this…. We can all disagree, and we’re never going to agree on everything, but this is just not ok. This is not politics as usual. This isn’t business as normal. This is like our world is on fire and we need to put it out. All I knew was that no one in Sarajevo or from Sarajevo was sleeping well.

By Melissa Walsh

Last night I dreamt there was a large snake in my house. It looked poisonous, dangerous, until I noticed a gentle look in its eyes. I felt a maternal empathy for it. “It’s not harming me,” I thought. “I’ll let it live in peace.” My German Shepherd then lunged and attacked it. I fled the suffering, feeling powerless to save the creature from the jaws of my dog. When I re-entered the room, I saw no sign of the snake. I looked under furniture expecting a gory mess of pieces of snake butchered by my dog. I found nothing. Then I realized my dog also was missing. I woke up, relieved that it was a bad dream. At the same time, I was grateful for sleep. I suffer too many sleepless nights. When I lived in Sarajevo more than 30 years ago, I remember hearing women chatting, whom I guessed to be in their fifties, the age I am now. They would greet each other each morning with queries about sleep. Dobro jutro. Da li si dobro spavala? “Good morning. Did you sleep well?” (They did not ask, “How are you?” as American women commonly do.) Oh. Nisam. “Oh. No, I did not.” Then a statement followed explaining why. Moj sin ne moźe naći posao. “My son can’t find work.” Or Imam bolove u kolenu. “My knee hurts.” A conversation about the problems the women faced affecting their sleep continued onto the streetcar. Bosnian novelist and 1961 Nobel Prize winner Ivo Andrić wrote about sleeplessness in several of his diary entries, which he published as Signs by the Roadside. “The night is our world, and sleeplessness is our faith, our homeland and our bread,” Andrić wrote. “We do not know, hear or see one another, but we share the same dwelling, without name or form, somewhere half way between the world of the living and the world of the dead, both equally close and equally distant, so that they cannot be summoned, glimpsed or comprehended. “We are not attached by anything except the fact that we are not attached to either the world of the living, or the sleeping, or the dead, or between ourselves. Without number, shape, name, relations, bonds or laws, we are nothing but suffering, nothing but the desire not to suffer, and to resist if we have to suffer. “And sleep or waking scatter us and obliterate us forever, as though we were a mysterious, rare game of light and darkness which no one has seen and which has not known itself, but which is reborn every night.” Andrić, who was born in Austro-Hungarian-occupied Bosnia, in a village near Travnik, in 1892 lived through two world wars. He was a student in Sarajevo and a member of Mlada Bosna, the “Young Bosnia” student movement, in 1914, when fellow member of Mlada Bosna, Gavrilo Princip, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife, Sophie. Andrić was arrested, but not convicted. He spent the duration of the First World War in prison or under house arrest. During World War II, Andrić wrote the novel The Bridge on the Drina, a popular work in his cannon of fiction and essays that earned him Nobel Prize distinction 16 years later. It’s no wonder Andrić wrote about sleeplessness. He was an intellectual caught up in politics that led to the death of his class mates as a young man. He was witness to occupation by a foreign power and to civil war — costly and deadly to countless innocents. For him and his contemporaries in Yugoslavia, nightmares became the truth of day. “The slightest and vaguest of all states, sleeplessness, has the firmest, double foundation,” Andrić wrote in his diary. “And a person who no longer has the strength to stay awake or the possibility of falling asleep is not saved from any of the misfortunes that can befall him. So he lies and fades away like a corpse without a shroud and at the same time he seeks answers to all the questions which life poses and with which it persecutes us. He has nothing, anywhere, but he feels his blood, love, strength and possessions steadily draining away from him with every moment.” Yugoslavia’s failing economy affected the sleep, even if indirectly, of these women I encountered at the streetcar stop in Sarajevo during the late 1980s. According to Susan Woodward in her heavily researched book about the political and economic factors leading to the disintegration of Yugoslavia, Balkan Tragedy, Bosnia, and most of Yugoslavia, suffered a rate of more than 20 percent unemployment. Close to 60 percent of those seeking work were adults under age 25. In a nation that valued higher education, offering it gratuitously to its residents, more than 38 percent of Yugoslavs under 25 were unemployed from the mid- through late 1980s. During those years, to repay national debt, Yugoslavia's politically conservative central government imposed rigid austerity federal policies, including increasing exports and limiting imports. Much of the population experienced a decrease in wages, coupled with soaring inflation. Political liberals sought reform by means of economic autonomy for the republics, which morphed into ethnic nationalism. What the West viewed and applauded in Yugoslavia as progressive reform towards a market-driven economy and democracy was tragically misunderstood.

What used to be known as the Serbo-Croatian language is now Serbian, Croatian, or Bosnian, which are linguistically the same language with variation in dialect. The word narod means both “nation” and “folk.” Therefore, when politicians spoke at rallies I witnessed there in person or on television in 1988 and 1989, calling for national independence, the interpretation by some hearers was a call for ethnic independence and territorial exclusivity and by others a call for regional community and multi-ethic unity. The interpretation by the hearer depended upon how radicalized politically he or she had become by unemployment and sky-rocketing inflation and to what degree the hearer was despairing over his or her financial prospects under Yugoslavia's strong central government, which annually rotated the head of federal leadership (the League of Communists) by republican representation, as well as how fed up the hearer had become with the promise in Yugoslavia’s 1974 Constitution of politically equitable sharing of a common Yugoslav economic pie.

Narodni rallies further radicalized the radicals. And in mid-1991, as the Yugoslav National Army combatted Croatia's move to secede and Serbs and Croats fought for ownership of territory in Croatia that they had previously shared in community, Sarajevans believed their multi-ethnic city, the tightly integrated capital of the most diverse republic in Yugoslavia, would remain peaceful. I was told this by friends in Sarajevo in their letters. (I left in 1989.) However, in March 1992, when the question of Bosnia-Herzegovina succession from Yugoslavia was put to a vote, Radovan Karadzić, representing a radical faction of Bosnian Serbs, boycotted the vote and declared a Bosnian Serb Republic, setting up Serb armed irregulars, who called themselves Četnik. The siege of Sarajevo began April 6, 1992, when 14 innocent Sarajevan civilians were killed by snipers hiding in the upper floors of the Holiday Inn. Among the six arrested in the hotel that day for these murders was Karadzić’s personal body guard. When I had traveled in Yugoslavia by train and bus from 1987 to 1989, I periodically heard chatter among fellow passengers that I found both troubling and absurd. I witnessed radicalized youth and foolish old men calling themselves Ustaša, if Croatian, and Četnik, if Serbian. They claimed they were rebels ready to kill their perceived ethnic enemies to preserve their narod. I never heard hate speech in Sarajevo. In her memoir about covering the Bosnian war while staying in an old residential area of Sarajevo, Logavina Street: Life and Death in a Sarajevo Neighborhood, journalist Barbara Demick, said she discovered that Sarajevans were caught off-guard by the war. “No wonder, then, that Americans were baffled by the Bosnian war. So were Bosnians,” Demick wrote. “The conflict was commonly defined as ‘ethnic warfare,’ yet everyone comes from the same ethnic stock. The difference among people is primarily in the religions they practice, yet to explain the fighting as a ‘religious war’ would be equally misleading, since most Yugoslavs were not religious people.” I was back in the United States then looking to return to Yugoslavia by way of a Fulbright Scholarship for graduate study in linguistics at the University of Novi Sad. I was granted the invitation, but it was cancelled a few months later — zbog rata, “because of war.” With a mixed population, communities in Vojvodina were under threat by extreme nationalist factions. My letters from Sarajevo were returned following the start of the siege, also with a note that included the phrase zbog rata. I wondered if my friends were among the thousands dead, the thousands imprisoned, the thousands being raped, or the thousands wandering and seeking refuge. I wondered about the Sarajevans I had seen daily at the university, the market, post office, streetcar. I wondered about the kids shown in the above image. All I knew was that no one in Sarajevo or from Sarajevo was sleeping well. “A man drowns in sleeplessness as in an ocean of dense, quivering darkness,” Andrić wrote, “and he is linked by only a breath like a slender thread to the white invisible world. “I do not sleep; I suffer, but I breathe.” Each breath is a gift. How difficult would it be to sleep knowing that your next breath might be your last, your hope and right to continue breathing extinguished by a sniper’s bullet or mortar fired from the hills of your valley? “Foreigners in Sarajevo urged one another to ‘be careful,’ Demick wrote, “but the Sarajevans were more likely to say, ‘Be lucky.’” For 30 years, the anxiety of wondering who among my friends in Sarajevo were unlucky keeps me awake some nights, as does the piercing in my heart over the past three years whenever I hear American radicals scapegoating and demonizing those they perceive as the other.

|

Categories

All

Like what you've read? Become a supporter.

Thank you.

Archives

June 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed